A Redlands Connection is a concoction of sports memories emanating from a city that once numbered less than 20,000 people. From pro football’s Super Bowl to baseball’s World Series, from dynamic soccer’s World Cup to golf’s and tennis’ U.S. Open, major auto racing, plus NCAA Final Four connections, Tour de France cycling, more major tennis like Wimbledon, tiny connections to that NBA and a little NHL, major college football, Kentucky Derby, aquatics and Olympic Games, that sparkling little city sits around halfway between Los Angeles and Palm Springs on Interstate 10. – Obrey Brown

It was June 15, 1983. In those days, that date served as Major League Baseball’s trade deadline.

Think of these great deals — Seattle traded Randy Johnson to Houston in 1998; C.C. Sabathia had been traded by Cleveland to Milwaukee in 2008; that same season, it was Manny Ramirez traded to Los Angeles by Boston; when the Mets got Yeonis Cespedes in 2015, the slugging outfielder led New York to that year’s World Series; Philadelphia dealt Curt Schilling to Arizona in 2000.

All of those deals probably outweigh that swap of second basemen in that 1983 trade between Seattle and the Chicago White Sox.

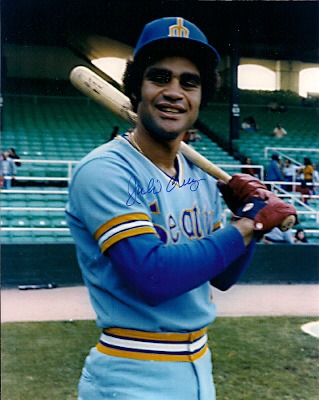

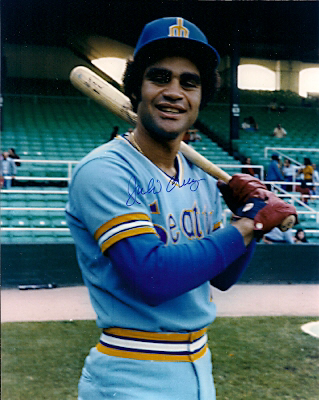

Julio Cruz, undrafted free agent out of Redlands High/San Bernardino Valley College, had been such a solid player for Seattle — a base-stealing dynamo, not to mention a flashy fielding second baseman.

A guy named Roland Hemond, the general manager in Chicago, noticed.

In 1983, Seattle took its sure-handed infielder and all-time leading base-stealer and dealt him to the ChiSox. That deal plucked second baseman Tony Bernazard from Chicago.

That mid-season trade, Chicago was five games under .500, fifth in the American League Western Division. Hemond pulled off thate Bernazard-for-Cruz trade, only real adjustment he made to an already-strong roster.

Hemond, a legendary general manager, made a trade that everyone would later credit with turning that season around. Looking to give his team a spark, Hemond’s trade launched an immediate effect.

I tracked down Hemond for comments on that trade. These were, of course, days before cell-phone usage, so getting hold of him seemed like a major achievement. Hemond was back east. That’s three hours’ difference than the west coast. I remember trying for a few days before I connected with him.

Why would I try? Local readership, no doubt. Every local reader might want to hear about their guy. Right? A little insight on those inner workings never hurt. We already had Cruz on the record.

“I was excited about the trade!”

“Chicago!”

“A real pennant race!”

“I love Seattle.”

That’s what Julio Cruz was telling me for that local press.

INTERVIEW WITH WHITE SOX GM

Hemond must’ve been in his office at Comiskey Park, home of the White Sox.

My standard intro … “Hi, Obrey Brown here from Redlands, hometown newspaper of Julio Cruz … wondering if I could pick your brain a little about that trade you made for Julio.”

Hemond, a friendly guy, needed no further prodding.

“Oh, hi,” he said. There were some pleasant formalities between us. Like this one: “Think you’ll make it out here to see him play?”

I had to fib on that one. That tiny budget of a Redlands newspaper had barely allowed me to cover a Terrier game in nearby Rialto or Fontana. Send me to Chicago? Said Hemond: “When you get here, look me up.”

If only, I thought.

“I think it’ll turn out to be a real great acquisition for this club,” said Hemond, whose East-coast accent was a nice touch to our conversation. “In fact, it’s already helped us.”

“How long have you had your eye on Julio?”

“Oh … no … wow. I’ve known about Julio for a few years. How can you not notice a guy with his glove and his ability to steal bases? No, he just didn’t jump off the page at us. We need this guy. We’ve known about him.”

Hemond said, “Our clubhouse needed a jolt. Tony (Bernazard) wasn’t all that great of an influence in there. I’ve heard a lot about Julio being a good guy.”

This baseball lifer, Hemond, was very gracious with his time. He asked, “Did you cover him while he was playing in high school out there?”

“No. I got here a few years after he left.”

I tried to stump him, though. “Julio’s coach out here was Joe DeMaggio.”

Hemond either didn’t hear me, or thought I was kidding. No, it wasn’t THE Joe DiMaggio (note the spelling difference).

COVERING THE ‘REDLANDS’ CHISOX

Those summer-time sports pages, though, got a big plug. Cruz, standing on second base, darted for home plate on future Hall of Famer Harold Baines’ sharp single to right field. Tenth inning. It was against the Angels. Game-winner. Division-clinching run. Celebration. Photos.

Huge splash in this Redlands newspaper.

Cruz was picked up from Seattle when the ChiSox were 28-32, fifth in the American League West. They went 71-31 with Cruz, batting ninth in that lineup with Rudy Law atop a strong White Sox attack.

That year’s White Sox were filled with superb batsmen. Baines, Ron Kittle, Greg Luzinski and Hall of Fame catcher Carlton Fisk, combined to hit 123 home runs. Law stole nearly 80 bases.

Their pitching was topped by LaMarr Hoyt and Rich Dotson, who won 24 and 22 games, compiling that league’s greatest number of wins by two pitchers. Southpaw Floyd Bannister was nearly unbeatable, finishing off that season with a 13-1 streak.

Second place belonged to Kansas City, which finished a staggering 20 games behind Chicago.

The Daily Facts kept a close watch on that “Redlands” White Sox. Remember, this was A Redlands Connection.

By that year’s All-Star break, those ChiSox had climbed to three games over .500. Then things really got hot. Chicago, led by Tony LaRusso managing, climbed into first place on July 18 and never looked back. Their second half record was 59-26, a .694 winning percentage.

Not everyone was impressed. One out-of-town writer dismissed that team as no better than fifth best in that year’s A.L. East. Texas manager Doug Rader theorized that ChiSox’s bubble had to burst. “They’re not playing that well. They’re winning ugly.”

On September 17 at Comiskey Park, the White Sox clinched Chicago’s first championship in 25 years. Baines’ single brought home Cruz with that game’s winning run.

BIRDS TOOK OUT CHICAGO IN PLAYOFFS

Chicago’s opponents in that playoff duel would be Baltimore, having won that year’s season series against the ChiSox, seven games to five. In that 1983 playoff matchup, the Orioles won three out of four.

Even with Cruz , that group of White Sox couldn’t shake Baltimore. Hall of Famers Cal Ripken, Jr. and Eddie Murray, plus a strong corps of pitchers ousted Chicago and ended up beating Philadelphia in the World Series.

The ex-Terrier hit .333 in four games, the White Sox winning game one, 2-1, before the Orioles came streaking back to win 4-0, 11-1 and 3-0 behind strong pitching from Mike Boddicker, Tippy Martinez and Mike Flanagan.

As for Hemond, that slick transaction for Julio may have gone a long way in snagging his second Sporting News Executive of the Year honors.

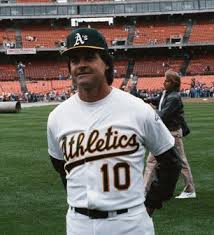

Years later, ’83 White Sox manager Tony La Russa and I were eyeball to eyeball in spring training Arizona. By this point, he had moved on to manage the Oakland A’s. I couldn’t help but try and snag him for some comments – even though it was years later – on Cruz.

La Russa didn’t have much time. Calling Cruz “an igniter,” La Russa wasn’t in a mood to chat. He said, “The thing I remember from that team was the power we had … Julio and Rudy Law gave us another dimension to score runs with their speed.”

One final, quick comment: “He played a great second base for us.”

Footnote: Seattle lost 102 games in 1983.

Sabathia, Johnson, Ramirez and all the other more famous MLB trade deadline might draw more attention in baseball’s history book. For the Chicago White Sox, however, that deal might be No. 1.