A Redlands Connection is a concoction of sports memories emanating from a city that once numbered less than 20,000 people. From pro football’s Super Bowl to baseball’s World Series, from dynamic soccer’s World Cup to golf’s and tennis’ U.S. Open, major auto racing, plus NCAA Final Four connections, Tour de France cycling, more major tennis like Wimbledon, tiny connections to that NBA and a little NHL, major college football, Kentucky Derby, aquatics and Olympic Games, that sparkling little city sits around halfway between Los Angeles and Palm Springs on Interstate 10. When this coach showed up to begin his legendary coaching career, there was no such freeway. He eventually became Team USA’s Olympic track coach. – Obrey Brown

It was May, 1984 – an Olympic year.

Jim Sloan, an heir to the R.J. Reynolds tobacco dynasty, was a celebrity photographer from Redlands. He pushed an invitation on me. There was a group of guys getting together for a reunion, of sorts. It was at Robert Scholton’s home, truly an athletic pioneer of Redlands. Citrus groves and all. Scholton had married into the Walter Hentschke family – one more Redlands-area pioneer.

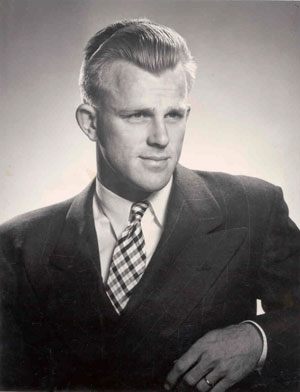

At this reunion, however, Payton Jordan was guest of honor. Sloan, Scholton & Co. wanted this reunion covered in their local newspaper. I wasn’t invited as a friend to chat and eat. I was invited to write up this guy.

One night earlier, it had been “Olympic Night” at Redlands Country Club. Naturally, Jordan, who didn’t exactly speak on golf, was their featured speaker. That “club” was directly across from Scholton’s home.

Scholton, Sloan and a bunch of buddies had invited Jordan to Redlands. He’d been around plenty. This visit, however, was special. Plenty of guys had been summoned for this reunion. It was an Olympic year, after all. Jordan had plenty of connections to Olympians.

Way back in 1939, before World War II, Jordan had coached at Redlands Junior High School. He’d just graduated from USC, so his coaching career was just getting underway. Little did anyone know.

That junior high campus had been located right across Citrus Ave. from Redlands Senior High – that is, before the two campuses were merged into one full high school. Eventually, Redlands Junior High was nixed.

After World War II, Jordan returned – briefly.

Jordan had been a high-achieving two-sports star at USC – part of an illustrious Trojans’ football team, later starring on their nationally prominent track team as a sprinter. He was from nearby Pasadena, where Mack and Jackie Robinson had grown up, but attended UCLA.

Jordan had been coached in football by the illustrious Howard Jones – brilliant record, 121-36-13 – who’d been Trojans’ coach from 1925-1940.

Track coach Dean Cromwell, USA’s Olympic coach in 1948, might’ve been even more prominent. USC guys that he coached, including Jordan, were too numerous to highlight.

Jones and Cromwell are both Hall of Famers in multiple spots, not just at USC, either.

JORDAN’S CONNECTION TO REDLANDS

It’s important to note that scintillating connection between Jordan, USC and Redlands.

It was easy to see why Jordan was so highly favored around Redlands. Scholton, Sloan & Co. were his “boys.” When Jordan showed up just before World War II, his background must’ve seemed spectacular in this small-town haven.

A USC guy in Redlands? Years later, Jordan had only added to his lengthy list of achievements. Talk about a Redlands “connection.”

Once I’d arrived at this glorious 1984 Redlands Junior High reunion, held at Scholton’s old-century, country club-style residence, I was only aware that Jordan had been 1968 Olympic coach – nothing else.

Jordan, splendidly dressed and warmly received by about a dozen older men – now retired, some with money, nice careers – couldn’t have been more gracious.

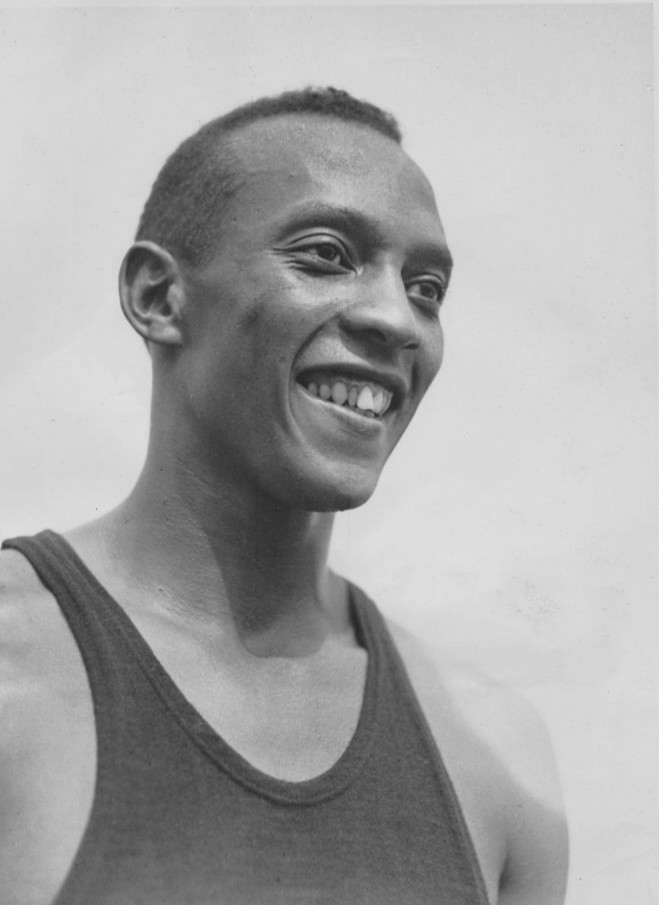

Throw this in: Jordan personally knew 1936 Olympic hero Jesse Owens.

Athletically, Owens was remarkable. In 1938 and 1939, Jordan shined on USC’s national championship track team.

- That 40.3 clocking in their 4 x 110, raced in 1939, was a world record Owens helped perform.

- Also in 1939, Jordan played on USC’s Rose Bowl-winning football team, 7-3 winners over Duke.

- In 1941, Jordan won the AAU 100-yard title – running sizzling 9.4 or 9.5 in yardage races, or a 10.4 in metric events.

- By his Senior years up to age 80, Jordan was an age-group champion and record holder in Masters meet – refusing to stop competing.

As an athlete, Jordan missed out on the 1940 and 1944 Olympics due to World War II. No doubt he’d have made those Olympics. Imagine those Redlands Junior High students, not to mention their athletes, getting a grip on their Olympian.

Jordan’s career had been phenomenal, to say the least.

His collegiate football exploits were spectacular. On that track, he’d been a whiz. After World War II, where he served U.S. Navy, it was time to get rolling in a coaching career.

CAREER HIGHLIGHTS TOO NUMEROUS

After coaching those guys at Redlands Junior High, Jordan landed at the collegiate level. It turned out to be venerable small-college Occidental, located in Eagle Rock, next to Pasadena – a key rival for that campus known as University of Redlands. It was like a hometown job for him since Jordan was a Pasadena product. After that Occidental decade between 1946 and 1957), there were nine outright conference track titles and one tie. Next stop was Stanford University’s over 23 more seasons.

Imagine. It all started at Redlands Junior High.

Also imagine:

- Billy Mills’ remarkable upset win at the 1964 Tokyo Olympic 10,000.

- Bob Beamon’s world record long jump, 29-feet, 2 ½ inches at the Mexico City Olympics.

- One of his Occidental athletes, Bob Gutowski, set a world pole vault record (15-9 ¾).

- Discus superstar Al Oerter nailed down his third and fourth gold medals under Jordan’s watch.

- When Jimmie Hines won the 1969 Olympic gold medal in a world record 9.9 seconds, Jordan was head coach.

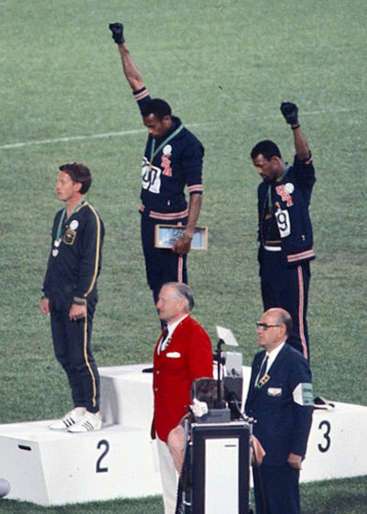

- Tommie Smith’s 200-meter gold medal in 19.8 seconds led to the “power salute” protest in those ’68 Games. It included third place finisher John Carlos.

- Quarter-miler Lee Evans set a world record 43.8 seconds in winning the 1968 Olympic gold medal.

- At those 1960 Olympic Trials, Jordan ran USA’s squad in a meet at Mt. San Antonio College in Walnut, Calif. No fewer than seven world records were set.

- During that 23-year career at Stanford, Jordan’s Indians (now Cardinal) had produced seven Olympians, six world record holders and six national champions.

This is just a small sampling of the exploits of the man I was sitting next to at Scholton’s home in spring 1984. At the time, I’d known none of all those achievements.

If I’d been paying attention to my TV set in 1968 – watching the track portion of that the Olympics, maybe I’d have noticed the interview with ABC’s well-known broadcaster.

From the left among athletic medal winners, Australia’s Peter Norman, Tommie Smith and John Carlos in the Olympic medal ceremony at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics at which the two Americans were protesting the poor treatment of Blacks in the U.S. (photo by Wikipedia Commons).Media had treated Jordan favorably, except for one nasal-toned, often exasperating, yet highly entertaining sportscaster from New York.

“Howard Cosell,” said Jordan, “had his mike in my nose while my foot was in his fanny. He’s the only one I had trouble with. I had him escorted out of the stadium.”

Guess I’d better be careful in my interview.

Here’s some evidence on how Jordan and Scholton were close:

Jordan once offered Scholton to help him coach at Stanford. The year, 1957. Scholton, a 1937 University of Redlands graduate – Pi Chi, track, cross country, biology major – was a teaching contemporary of Jordan’s at Redlands Junior High.

Scholton, according to folklore, had served under NFL legend George “Papa Bear” Halas during his own U.S. Navy stint. In Redlands, Scholton taught biology, coaching runners in both track and cross country.

More folklore came after Jordan took that Stanford job, apparently offering Scholton an assistant coach’s role to his former contemporary. Homegrown, however, Scholton stuck around Redlands.

That association between Scholton and Jordan, however, lasted for years. Scholton retired in 1970. Jordan called it quits in 1979.

A curious note: As the Olympics were set to take place in Los Angeles, Jordan conceded he wouldn’t be attending. “I don’t have tickets.”

Scholton, however, had blocks of track & field tickets at the Coliseum. I bought a couple from him for me and my father-in-law, Dean Green – an assistant principal RHS, of all places, in an office that was on the same side of the street where Redlands Junior High School once existed.

A portion of my 1984 interview:

“LET THE GAMES BEGIN”

Jordan says it might be a euphemism for “Troubled Times.”

“The Olympics,” he told me, “are always the focal point of politics, world unrest and controversy. All the problems of the world seem to be magnified during this period of time.”

PERFORMANCE ENHANCING DRUGS

“You can make it without steroids,” said Jordan, who knew plenty of athletes even back in those days. “You don’t have to do it … If you’ve got the ability, work harder, eat better and dedicate yourself, you’ll get there.”

AMATEUR VS. PROFESSIONAL

“There is no such thing,” he said, “as amateurism.”

All normal workings of any Olympic disagreements are simply workings of non-athletes seeking to control that athletic world.

JESSE OWENS

History records that Hitler turned his back on that one time Ohio State star at those 1936 Berlin Olympics. Said Jordan: “Actually, it wasn’t Owens that Hitler had turned his back on. He’d shunned Cornelius Johnson after he won the high jump the day before.”

Germany long jumper Lutz Long, Jordan proclaimed, had given Owens a tip that helped lift him to win that fourth gold medal in Berlin.

“Those types of incidents,” said Jordan, “were left under-publicized, in comparison to what activities existed between non-athletes.”

In 1968, Owens had been summoned to Mexico City for a bull session with the team. “There’s nobody I know who’s less of a racist than you,” he told Jordan. “Anything I can do, just ask.”

BLACK POWER MOVEMENT

Smith and Carlos, it had long been rumored, were set to protest at an Olympics in which several black U.S. athletes had decided not to participate – perhaps in their own protests.

It’s one reason why Cosell was so blatant into Jordan’s face during those ABC interviews.

“They would’ve come to me to discuss (the protest),” he said, “and I would’ve vetoed that idea. They did come in and asked, ‘What should we do?’ I said, ‘Let me and my staff handle it.’

“Thank God it worked out beautifully.”

Part of that was Smith and Carlos were suspended from USA’s Olympic team and sent home.

It was a team, Jordan said, that was very close. “I never experienced that kind of closeness in spite of all the distractions. It was a group of people … who didn’t get hysterical about it and lost sight of our mission.”

Jordan says he took no part in any protest movement. “I was part of it, though. I was the coach.” Evans, Carlos and Smith, he confided, “were probably more loyal to me.”

That USA team came out of 1968 with more gold medals and Olympic records than any prior Olympic team, plus several future years.

After several minutes of that memorable Olympic protest chatter, there was a likely conclusion on talking it over. Too much to chat over. Jordan leaned back in his Scholton home chair, frowned and said, “I think that’s enough talk about 1968.”