Redlands Connection is a concoction of sports memories emanating from a city that once numbered less than 20,000 people. From the Super Bowl to the World Series, from the World Cup to golf’s U.S. Open and the Olympics, plus NCAA Final Four connections, NASCAR, the Kentucky Derby and Indianapolis 500, Tour de France cycling, major tennis, NBA and a little NHL, aquatics and quite a bit more, the sparkling little city that sits around halfway between Los Angeles and Palm Springs on Interstate 10 has its share of sports connections. “Willie, Almost Mickey and The Duke?” Here’s one that was in Redlands. – Obrey Brown

REDLANDS – That was Jordan Snider out in center field, wearing jersey No. 44. The site was The Yard, home field for home team University of Redlands. Snider was a senior member of that Bulldog baseball squad.

Temecula Chaparral High, located about an hour’s drive from Redlands, was where this right-handed ballplayer had come from only a few years earlier.

Batting .295 in 2008, .361 as a sophomore in 2007, .252 in his frosh season right out of the Pumas’ varsity program, where he’d hit .305 with two HRs for his Temecula prep.

Starting all 36 games as a Bulldog senior in 2009, he’d played four straight seasons with winning teams, hitting .321 with 4 homers.

So who watched him play? His grandfather.

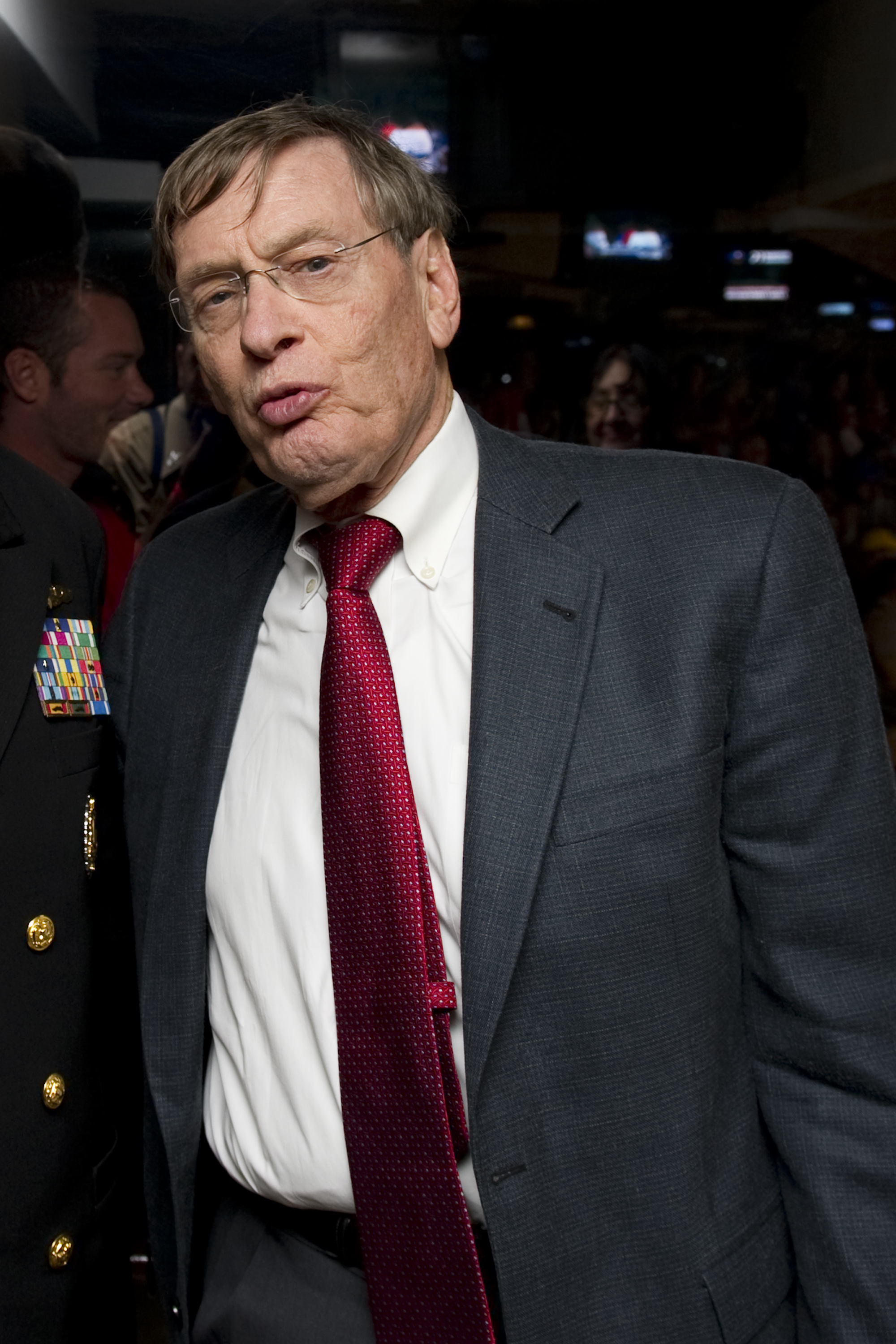

I’d shown up to chat with University of Redlands baseball coach Scott Laverty. Game still taking place. I’d have to wait. Sitting along first base bleachers, I took a seat near an older gentleman, wearing a hat to keep his head sun-free.

Seemed to be a nice guy. You run into that occasionally at ball games. Nice guys. Friendly. Talkative. It’s always fun to talk a little baseball, right?

After that game, I approached Laverty for a little post-game chat. We talked a little about their game. At one point, he said, “I saw you out there talking to Duke.”

Duke?

There was no need to explain. The second he said that, I knew he’d meant Duke Snider. That kid in center? Snider. A guy sitting and watching? Duke? It all came together like clockwork.

“Duke.”

Something told me. I was a little tongue-tied, though. I’d been talking to a baseball Hall of Famer and didn’t even know it. I was a little ashamed.

“That’s his grandson out there in center field,” said Laverty.

Well, that adds up, doesn’t it?

It was a Snider from Temecula.

Edwin “Duke” Snider, Duke of Flatbush, lived a little south of Temecula. His grandson was all-conference one year. A good fly-chaser out in center – just like his grandpa.

There might’ve been something symbolic about Jordan wearing No. 44, especially since his grandfather wore No. 4 in Brooklyn for the Dodgers. A double tribute, most likely.

DUKE OF FLATBUSH ORIGINALLY FROM COMPTON

That Duke of Flatbush really came from Compton, Calif. At the end of his life, he lived near the San Diego County city of Fallbrook – a nice retirement area.

A couple games later, I showed up at Redlands looking for Duke. Sure enough, he was there. “Do you have a minute?” I asked him.

You always hesitate when asking someone – a Hall of Famer, celebrity, well-known name, you know – if they’d mind an interview. He was there to watch his grandson who, at that moment, was playing in that same part of a ballfield he’d played in 45 years earlier.

“For crying out loud,” I could just hear anyone say, “I’m here to watch my grandson play. Maybe later.”

But Duke didn’t say that. Brooklyn, L.A., New York Mets and, finally, the Giants in San Francisco. Those are teams he played.

I’ve got to say it. There was nothing all that special about this interview. My questions would’ve been stale and useless. What do you ask a guy like that? Nothing that hasn’t been asked a hundred times before, right?

I settled on an angle about how he finished his career in a Giants’ uniform, 1964. Sold to San Francisco by the Mets. I tried to have a conversation rather than an interview.

“I can’t say I was all that upset at the trade,” he said at Redlands’ The Yard with a few people listening to our chat. “I was friends with a lot of those guys, anyway, Willie (Mays), Al Dark (Giants’ manager), Don Larsen …”

Besides, he said, “I lived out here on the West Coast.”

Oh, man – Don Larsen! The guy who’d pitched a perfect game against the Dodgers in the 1956 World Series? How many times must he’d have been asked about Larsen? Snider went 0-for-3 in that game.

I skipped that topic.

Did he remember his last home run?

“I do,” he said. “Candlestick Park. San Francisco. Jim Bunning, a very good pitcher. Yeah, that was my last one. Only hit four that year. Fourth of July game. I never hit another one.”

That was his 407th. It was a first-inning homer, a two-run shot. “Jimmy beat us that day.”

You play much center field?

Duke laughed. “For the Giants? You’re kidding. Not quite. Somebody named Willie Mays was already playing there.”

Both of us chuckled. Though he was mostly a pinch-hitter, Duke said, “I played either left or right.

“I remember being in the lineup one day … can’t remember where we were playing, though. Al had me leading off. Mays was second. McCovey was third and Cepeda was hitting clean-up. What’s that? A couple thousand home runs between us, or something like that?”

Mays at 660, McCovey’s 521, Duke’s 407 and Cepeda’s 379 equals 1,967 lifetime bombs. There may not have ever been another quartet in major league baseball hitting back-to-back like that with those kinds of impressive numbers.

Said Snider: “I can’t remember anything about that game, though – who won, nothing.”

Upon reflection, I should’ve asked him about Jackie Robinson.

Or Leo Durocher. Roy Campanella. Gil Hodges. Don Newcombe. Sandy Koufax, mystery man who rarely does media interviews.

Or playing in six World Series, winning twice.

That would’ve been a nice tack. What was it like to have Koufax on the Dodgers for those six or seven years before he started blazing away?

Never got another chance, either.

A few years later, the Duke died in Escondido.

We’d talked baseball in Redlands.