A Redlands Connection is a concoction of sports memories emanating from a city that once numbered less than 20,000 people. From pro football’s Super Bowl to baseball’s World Series, from dynamic soccer’s World Cup to golf’s and tennis’ U.S. Open, major auto racing, plus NCAA Final Four connections, Tour de France cycling, more major tennis like Wimbledon, tiny connections to that NBA and a little NHL, major college football, Kentucky Derby, aquatics and Olympic Games, that sparkling little city sits around halfway between Los Angeles and Palm Springs on Interstate 10. – Obrey Brown

It was June 1, 1995. The place was Knoxville, Tenn.

Patrick Johnson, born in Georgia, moved to Redlands, took a football scholarship at the University of Oregon, eventually winding up playing NFL professionally in Baltimore. All evidence pointed to a possible world-class career on that track. There was a moment, though. In college. Here he was in Tennessee. World class speed seemed to be everywhere.

Johnson, an Oregon freshman, was competing against the likes of Ato Boldon, Obadele Thompson, Donovan Powell and Tim Harden, among others. A month earlier, Johnson had beaten Olympic legend Carl Lewis in nearby Des Moines, Iowa.

On hand was the NCAA Division 1 championships, hosted by the University of Tennessee between May 31-June 3.

As a world-class speedster, Johnson never hid from the fact that his first interest in athletics was football. I’ll never forget that moment, either.

“All I wanted to do,” Johnson told me during his senior year at Redlands High in 1994, “was play football. That was my goal. Man, I loved track. But football was something different. It was special.”

It was one of a few chats with, perhaps, one of Redlands’ most accomplished athletes.

Here he was, the reigning track & field star at Redlands in 1994 – the eventual state 100- and 200- meter champion. His times were outrageously quick – a 10.43 to win the 1994 State 100 title, while a 10.61 was quick enough to win the Southern Section Division 1 championship.

Don’t forget the 200, where he turned it on three times to win titles, starting in 1993 with a 21.40 to win the Division 1 championship.

One season later, he not only re-captured the Division 1 title in 21.25, but he beat all comers at the State finals in 21.01.

He was no marginal athlete in either sport. Compared to football, where his skills could’ve been used in a variety of positions on the field, Johnson single-mindedly trained for football – even during spring track season.

That’s the groundwork for Johnson’s upcoming track career. Right?

Even the most casual observer might agree that Johnson’s future seemed to be on that oval that usually surrounds any football field.

As a freshman at Oregon, Johnson beat all comers in the Pacific-10 400-meter finals – 45.38 seconds. He made the NCAA Championships in Knoxville, Tenn. that year, unable to qualify in either the 100 or the 200.

His competition was off the charts.

Guys like Bolden, of UCLA, was winning the 200 in 20.24. Johnson’s prelims time was 20.82 – ninth place, one spot out of a place in the finals.

At least Johnson made the 100-finals. But his 10.32 clocking was eighth, and last, in a field headed by Kentucky’s Harden (10.05). In that race was the Jamaican, Powell, whose brother, Asafa Powell, once held the world record (9.74) in the 100.

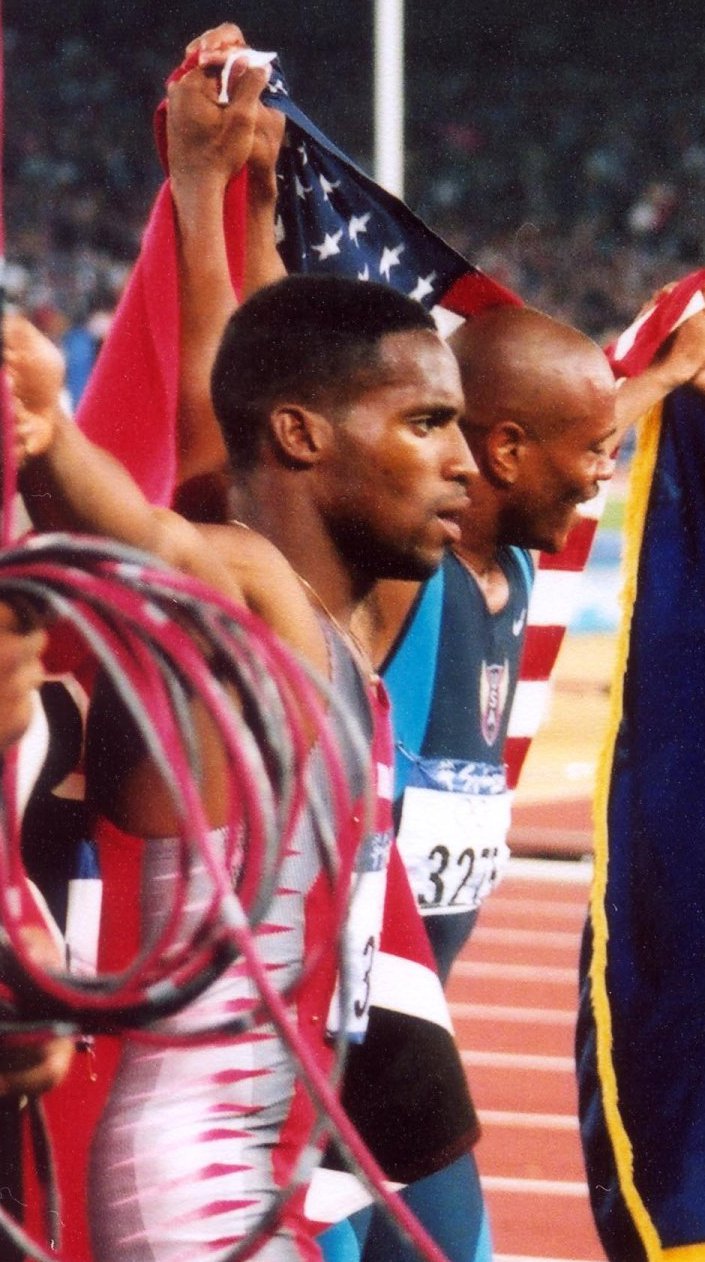

Harden was part of the Olympic silver medal 4 x 100 relay at the 1996 Atlanta Games.

Boldon, an eventual four-time Olympic medal winner, had false-started in that 1995 100 semifinals, eliminating him from a possible sprint double – a controversial result, in fact.

A month, or so, before that year’s NCAAs, Johnson prepped at the Drake (Iowa) Relays – on April 29, 1995. It was there that Johnson beat nine-time Olympic gold medalist Carl Lewis across the line in the 100-meters. Few recall, however, the Lewis’ career was coming to an end. Or that Johnson didn’t even win that race.

Thomson, a sophomore at Texas-El Paso, won in 10.19. Johnson, an Oregon freshman, was next at 10.26. Lewis, the Olympic hero, was third in 10.32.

SPEED KILLS ON A FOOTBALL FIELD

Johnson’s speed was a rampant weapon on any football field.

In football at Redlands, Johnson never seemed to have that huge, stunning, break-out game that observers would recall in years to come. That never kept him from swaying from his dream.

“Ever since I was little,” said Johnson, “I’ve thought about football.”

His Redlands track records will likely stand the test of time – 10.39 in the 100, 20.79 in the 200, 43.79 in the 400 and anchoring a 4 x 400 relay (3:18.79) are numbers that just don’t point a young man away from track & field.

The tipoff should have been easy to spot.

Upon Johnson’s transfer to Redlands as a junior in 1992, he was declared ineligible because he did not have enough units toward graduation. In Terrier coach Jim Walker’s first season, Johnson was a practice squad player from weeks one through 10. Under those conditions, it would have been easy to find something else to do.

“I remember coaching the defensive backs that season,” said onetime Redlands assistant Dick Shelbourne, “the season Pat missed playing in the games because he was ineligible. He only missed two practices the whole season.”

It was a sure sign to Terrier coaches that Johnson was serious about football. When the playoffs rolled around, Walker and Shelbourne worked him into their games against Capistrano Valley and Loyola – in the secondary.

That was Redlands’ introduction to Johnson, who was eligible to run track later that spring. By his senior year, Walker contemplated Johnson at any one of three different offensive positions – receiver, running back or an option quarterback.

Settling on running back, Johnson’s season was uneventful – 583 yards rushing, another 257 receiving, and the Terriers failed to reach the post-season.

His speed on the track lured interested parties because he played football, too. Johnson opted for the University of Oregon, where he played wide receiver.

Years later when Ducks’ football coach Rich Brooks spoke about Johnson, he chuckled when we chatted. “That speed of his,” he said, “could’ve taken him anywhere – football or track.”

Let’s not forget, either, that Oregon is home to Hayward Field, which is the nation’s top site for track & field. It would be impossible not to feel that emotional tug. He seemed offended if anyone suggested track over football.

He’d shake his head. Mind was made up.

FOOTBALL NUMBERS VERSUS TRACK TIMES

At Oregon from 1994-97, Johnson snagged 143 passes mostly from the likes of Ducks’ QBs Tony Graziani and Akili Smith. His final collegiate game, against Air Force in the Las Vegas Bowl, Johnson took advantage of his blazing speed. Catching five passes for 169 yards, he caught two TD passes from Smith for 69 and 78 yards.

On the other hand, he remains on Oregon’s all-time records list – eighth best in the 100 (that 10.26 at The Drake Relays), tied for second best in the 200 (20.39) and sixth best in the 400 (45.38) – with all electrifying marks.

Remember, this is a historic collegiate program. Ranking among the best at that school is overwhelming.

Though uniquely qualified to take on the world’s best sprinters of the day – Lewis, Michael Johnson and Maurice Greene, among others, Johnson’s chosen field was professional football.

The Ravens made him the 42nd selection in the draft, taken in the second round of the 1998 NFL draft.

Johnson, a two-time NCAA All-American in the 100 and 200 in his only full season of collegiate competition, was expected to win the 400 NCAA championship in 1996.

Plus, he was a staunch favorite to make the USA Olympic team that year.

Remember, The Games were scheduled for Atlanta, Ga., Johnson’s home state.

It’s possible Johnson might have over-trained early that season – trying too hard, perhaps. He was, apparently, in no condition to compete at the NCAAs.

Johnson took second in the Pac-10’s 400-meter finals in 1996.

Those calamities added up. Johnson never stepped on Hayward Field’s track again to compete.