A Redlands Connection is a concoction of sports memories emanating from a city that once numbered less than 20,000 people. From pro football’s Super Bowl to baseball’s World Series, from dynamic soccer’s World Cup to golf’s and tennis’ U.S. Open, major auto racing, plus NCAA Final Four connections, Tour de France cycling, more major tennis like Wimbledon, tiny connections to that NBA and a little NHL, major college football, Kentucky Derby, aquatics and Olympic Games, that sparkling little city sits around halfway between Los Angeles and Palm Springs on Interstate 10. In this case, a professional bowler was on his way from Torrance, California and now stopping on his way to a spot in Arizona. Went along with I-10 to get him there. – Obrey Brown

There was, by huge surprise, a mid-afternoon telephone call. I worked at a newspaper in Redlands. Mid-summer, 1982. Middle of the week. Very little was taking place around this city. Guys like me are always looking for a story. Well, here one was.

In those days, telephone calls were the lifeblood of any newspaper reporter. Most of the time, when callers weren’t complaining or spouting off, good calls often proved exotic and helpful tips. One afternoon, a very quiet female voice at Empire Bowl, the local bowling alley, had an alert.

“Earl Anthony,” she said, “is here right now … bowling.”

Anthony, who would eventually turn into the first-ever $1 million career winner, was a legendary figure on the Professional Bowling Association tour.

Though I doubted the caller’s accuracy, what would someone like Earl Anthony be doing in Redlands, of all places, right? It wouldn’t take a whole lot of effort to drive a few miles from the office to verify this report.

Earl Anthony? In Redlands? Let’s find out.

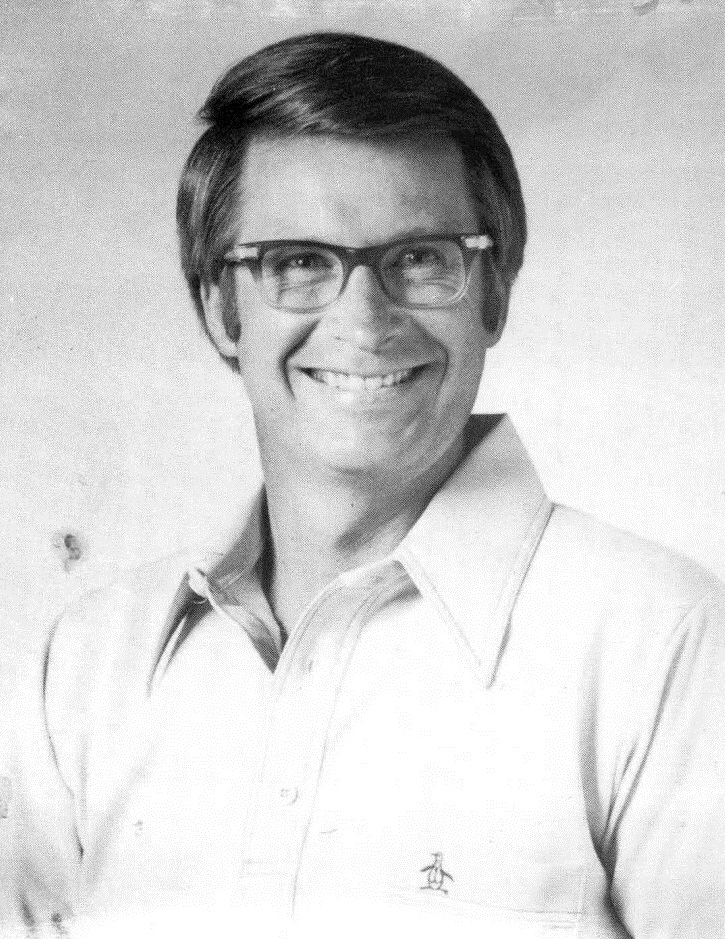

Earl Anthony, who missed the cut at a PBA tournament in Torrance, was on his way to another tournament in Tucson, Ariz. when he stopped off, at all places, Empire Bowl in Redlands (photo by Wikipedia Commons).Empire Bowl, located right next to a portion of Interstate 10, was in a fairly prominent spot along Colton Ave. It bordered along the North Side neighborhoods. A couple blocks west sat Bob’s Big Boy, a popular little restaurant. A little east was historic downtown Redlands.

I parked, got out, walked into the Empire. A crowd of people had converged to the far right portion.

That female tipster’s phone call turned out to be true. Suddenly, I became a bowling writer. I hadn’t written much on bowling. Our newspaper relied on people turning in results.

Sure enough, there he was, rolling a ball. Alone. A lefty, to be sure. Smooth. Effortless. Confident. There were plenty of local watchers viewing him not all that far away. I strolled down in front of all those folks.

“Earl, do you have a minute?”

That left-handed, bespectacled gentleman motioned me over. We chatted for a while. First question: What in the heck was he doing here? Earl Anthony, a legendary bowling ace, laughed.

“I’m just passing through,” he said. “Thought I’d stop and roll a few just to get some exercise.”

We became quick friends. He ordered us a couple Cokes.

It was small talk, mostly. Lots of PBA titles. Earlier that year, he became that first-ever $1 million dollar cash earner. One year earlier, he was a Hall of Famer. Some major championships. He’d been PBA Player of the Year a handful of times.

That million dollar reach, though, came against Charlie Tapp that earlier year. The PBA National Championship, I asked him, when he copped that big 1981 event. Anthony nodded, then started at a single pin – which he nailed, by the way.

Funny, though. Anthony shared the news that he, at one time, had been a left-handed pitching hopeful with the Baltimore Orioles’ minor league, along with a few other insights about his life.

“My pitching helped my bowling, though. It helped my rhythm and concentration.”

At Redlands on that particular day, he let a ball roll down that Alley 40 – again.

PRO BOWLING IS ROUGH

We chatted a little about local showboats. They have bowlers in every city. At every tournament. They’re the dominant rollers at their “House,” no doubt. Pro bowling stars roll into town and have to take those locals on. You know, kind of like gunslingers taking on the city’s fastest gun.

Anthony, 43 at the time, laughed. “Yeah. Yeah. Sure, I’ve faced those kinds of guys. A lot of times. Didn’t always win.”

He’d just missed the cut at a tournament in Torrance, “so I figured I’d better get out here and practice a little.”

Each week, the PBA’s top bowlers were in contention.

“Mark Roth, Mal Acosta and guys like that,” he said, noting other PBAs. “I don’t mean to put down any town’s best bowlers, but usually the difference between them and us is the same as a high school baseball player coming up to the big leagues.”

Referring to the rabbit squad, he noted, a rabid group of bowlers trying to qualify for one of those 144 tournament spots, he noted, “there were 200 to 300 guys trying to qualify for 60 or 70 spots. Trust me, we’ve got our eyes on everyone.

“When they qualify, they’ve made no money – just the right to play in the tournament.”

Pro bowling is tough, he said. At that time, Anthony told me, “pro bowling was at an all-time high in popularity. There is more television coverage than ever.”

In the early 1980s, ABC was televising 16 straight weeks of events.

At that very moment we were talking, the Pennzoil Open in Torrance – the tournament at which he’d failed to qualify – was set to televise on fairly new sports channel ESPN.

His home was in the Northern California city of Dublin, bordering the Bay Area. Acosta and Rich Carrubba, current PBA members, were connected along that area, too.

TOP PBA GUYS REACH OUT AT HIM

Ah, but Anthony spoke of a new PBA rule which required its members to take on a 2 ½ -day course – things like how to handle money, talk to the press and public, plus learning PBA history. He wasn’t all that pleased.

“I’m insulted by it,” he said. “I think it’s a great idea for guys coming out. But they want me and everybody else to go back and I think it’s ridiculous.”

I’d reminded him that professional golfers, upon inception in the 1960s, did not require its current membership to qualify.

Said Anthony: “I used that same analogy with the PBA. They’re not listening to any of that. They still want us to attend.”

Sarcastically, he added, “I’ve only been on the tour for about 13 years.”

In other words, he was history.

A few years earlier, 1978, he topped the field for his 30th all-time triumph – “the Tournament of Champions,” he quietly noted. It wasn’t much longer that year that this man suffered a heart attack. He returned, though.

Ah! Some conversation toward me led to more shooting along that wall-based, widest lane at Redlands’ action center.

ANTHONY CLOSING IN ON HIS GOALS

We sipped our Cokes. In between questions and answers, he’d effortlessly roll his ball down the lane. Here was a guy that made his living by rolling a ball better than most.

Before leaving, I said, “You know, I’ve never taken a photo before. Would you mind?”

“Not at all,” he said. “Tell me what you need.”

The photo came out a little dark. It was publishable. I think I was more excited about the photo than I was the article I’d written. Redlands’ bowling public would discover that a PBA star had stopped briefly in their community, en route to Tucson, his next tournament stop.

Two years earlier, Anthony had suffered a heart attack.

“I’m fine now. I just want to start winning.”

I was done.

On my way out, I stopped at the front desk. Spotted an older woman.

“Are you the one who called me?”

She nodded.

“I owe you dinner for that. Appreciate what you did.”

“I get off at 6.”

“Bob’s?”

“Should I meet you there?”

It was, it turned out, the first and last time I’d ever see her.

Because of her, though, I’d met – and interviewed – Earl Anthony.

Those telephone calls are what every newspaper reporter requires to make it work on the pages.