A Redlands Connection is a concoction of sports memories emanating from a city that once numbered less than 20,000 people. From pro football’s Super Bowl to baseball’s World Series, from dynamic soccer’s World Cup to golf’s and tennis’ U.S. Open, major auto racing, plus NCAA Final Four connections, Tour de France cycling, more major tennis like Wimbledon, tiny connections to that NBA and a little NHL, major college football, Kentucky Derby, aquatics and Olympic Games, that sparkling little city sits around halfway between Los Angeles and Palm Springs on Interstate 10. – Obrey Brown

Twenty-four years after Redlands’ Jim Weatherwax appeared in pro football’s first-ever title game between National Football League and American Football League champions, one of the most coincidental connections in Redlands’ Super Bowl-connected history took place.

A pair of ex-Terriers showed up in the NFL’s biggest game.

Brian Billick, whose Redlands High School days were beckoning when the first Super Bowl kicked off in nearby Los Angeles, had a future in the NFL’s big game.

Patrick Johnson, who caught a pass in Super Bowl XXXV, nearly made a diving catch for a touchdown in that same game against New York.

At Raymond James Stadium in Tampa, Fla., Baltimore Ravens – formerly a Cleveland Browns’ team – stopped New York, 34-7, to win Super Bowl XXXV. That date: Jan. 28, 2001.

All those football eyes from Redlands were squarely on those Ravens. By-lines appeared under my name about Billick’s early years in Redlands – his friends, starting football as a ninth grader at Cope Middle School, plus some of his Terrier playing days which included subbing for injured QB Tim Tharaldson in 1971.

Thirty years later, he was coaching Baltimore in Super Bowl XXXV.

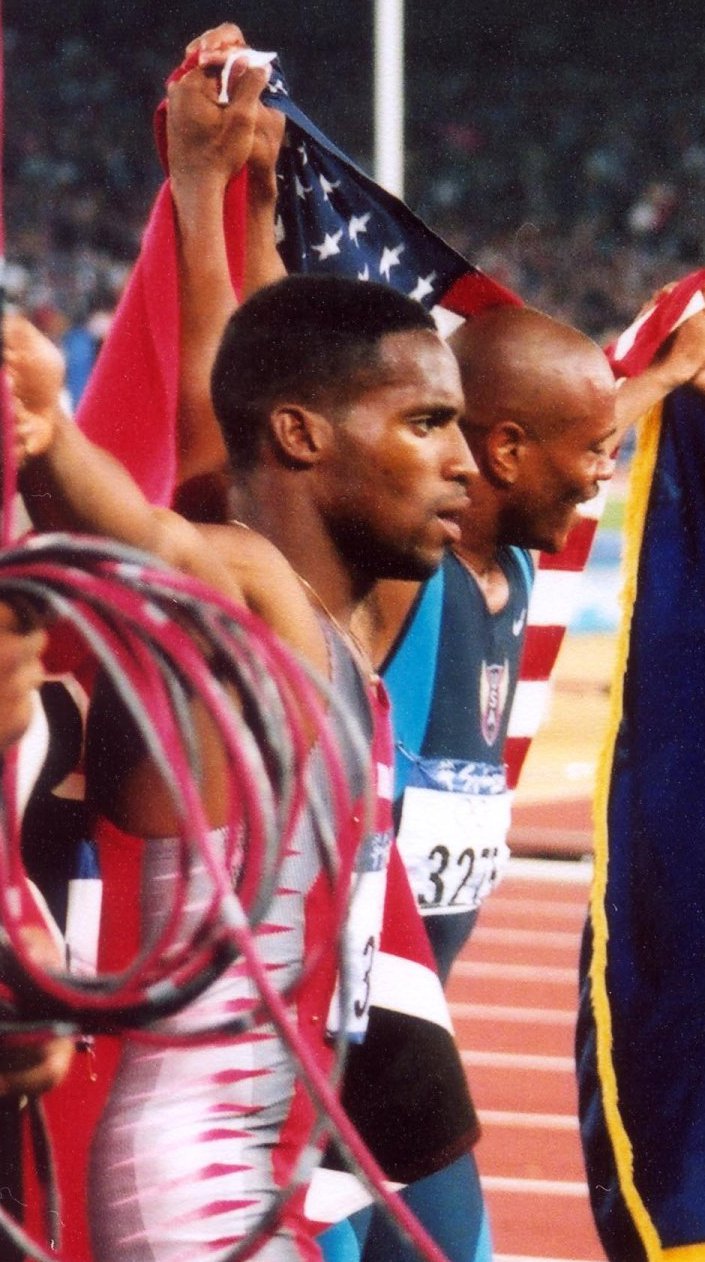

Johnson, a track & field sprinter who had raced to California championships in both the 100 and 200 less than a decade earlier, turned up as a second round pick by Baltimore in 1998. He wore Terrier colors. Picking football over track & field, Johnson was an Oregon downfield threat noticed by Baltimore.

It was during Johnson’s third season when Baltimore reached that Super Bowl. Twelve of his 84 career catches came in that 2000 season, two going for touchdowns. Tight end Shannon Sharpe (67 receptions, 810 yards, 5 TDs) was, by far, Baltimore’s top receiver. Running back Jamal Lewis (1,364 yards, 6 TDs) was that team’s most dangerous threat.

Baltimore’s defense, led by linebacker Ray Lewis, free safety Rod Woodson, end Rob Burnett and tackle Tony Siragusa helped keyed the Ravens’ drive to an eventual 16-4 record. Playoff wins over Denver, Tennessee and Oakland lifted Baltimore into the Super Bowl in Tampa Bay, Fla.

Billick’s high school coach, Paul Womack, traveled back east to see his former player. He showed up at the team’s Owings Mill practice facility. Basically, Womack had free run of the practice facility.

Womack heard Billick telling Johnson – dubbed the “Tasmanian Devil” for his uncontrollable speed – he had to run precise routes. The ex-Terrier coach quoted Billick, saying, “Pat, I can’t play you unless you run the right routes.”

In the Super Bowl, Johnson snagged an eight-yard pass from QB Trent Dilfer. It was good for a first down. There was another moment, though.

“I ran right by (Giants’ free safety Jason) Sehorn,” said Johnson.

Dilfer delivered the pass. Into the end zone. The ex-Terrier receiver dove.

“It hit my fingers,” he said. “It’s okay. It ain’t all about me.”

As for Johnson, I got him on the telephone a couple hours after that big win. He was on Baltimore’s team bus, sitting beside teammates Sam Gash and Robert Bailey. At that moment, Johnson said the Lombardi Trophy was sitting about six feet behind him.

“I just had it in my hands,” Johnson said, “right before you called.”

LOMBARDI, LANDRY, SHULA … BILLICK!

Billick, for his part, later shared time on the telephone with me, sharing some of his innermost thoughts for the benefit of Redlands readers. Baltimore beat Denver, Tennessee and Oakland to land in that Super Bowl.

“I can’t believe I’ll have my name on that trophy,” said Billick, days after that big event in Tampa. It was a chance to reflect on guys like Tom Landry, Don Shula, Joe Gibbs, plus a man he once worked for in San Francisco, Bill Walsh.

Billick named those legendary coaches he’d be sharing Super Bowl glory throughout the years.

After that game, that Lombardi Trophy was held aloft. On TV. Billick was holding it. Showing it to players. To fans. An Associated Press photographer snapped a picture. One day later, the Redlands Daily Facts’ single page sports section on Jan. 29, 2001 was virtually all Billick and that Lombardi Trophy. Confetti was falling all around him.

Framed around the Billick photo were two stories – one by local writer Richard D. Kontra, the other by-line was mine. As sports editor, I probably should have nixed the stories and enlarged that photo to cover an entire page.

Let the photo stand alone. Let it tell the whole story. As if everyone in Redlands, didn’t know, anyway.

One day after the enlarged photo, the newspaper’s Arts editor, Nelda Stuck, commented on why the photo had to be so large. “It was too big,” she said. “I don’t know why it had to be that big.”

Maybe she was kidding.

I remember asking her, “Nelda, what would you do if someone from Redlands had won an Academy Award? You’d bury it in the classified section, huh?”

That’s a newspaper business for you. Everyone’s got a different view of reporting.

A P.S. on Womack: Not only did he coach Billick in the early 1970s, but the former Terrier coach was Frank Serrao’s assistant coach in 1960. On that team was Weatherwax, who also played a huge role on Redlands’ 1959 squad.

It was a team that Serrao once said might have been better than Redlands’ 1961 championship team.

Another P.S., this on Weatherwax: While he had been taken by the Packers in the 1965 draft, the AFL-based San Diego Chargers also selected him in a separate draft. He played in 34 NFL games before a knee injury forced him from the game.

A third P.S., this on Johnson: Billick’s arrival as coach in 1999 was one year after Baltimore drafted the speedy Johnson. That would at least put to rest any notion that Billick played some kind of a “Redlands” card at draft time.

One final P.S.: That Jan. 29, 2001 Redlands newspaper headline in that Super Bowl photo was simple. To the point.

“Super, Billick.”