A Redlands Connection is a concoction of sports memories emanating from a city that once numbered less than 20,000 people. From pro football’s Super Bowl to baseball’s World Series, from dynamic soccer’s World Cup to golf’s and tennis’ U.S. Open, major auto racing, plus NCAA Final Four connections, Tour de France cycling, more major tennis like Wimbledon, tiny connections to that NBA and a little NHL, major college football, Kentucky Derby, aquatics and Olympic Games, that sparkling little city sits around halfway between Los Angeles and Palm Springs on Interstate 10. Cyclists from everywhere have ridden tons of roads all across the world, including in Redlands once per special year. – Obrey Brown

It was September 17, anniversary of a 2000 Sydney Olympic Games appearance.

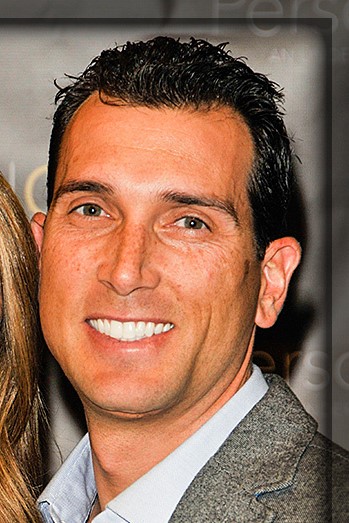

After nearly four decades from Redlands Bicycle Classic mastery, a Johnny Bairos story might fall somewhere through those cracks. To this date, Bairos is that lone local cyclist who had ever found himself standing on a podium – first in a stage – after winning a downtown Street Sprint Prolog.

He was, in fact, going to be an Olympian. Bairos was considered a speed-whiz on a bike. He wasn’t a road cyclist or a criterium specialist. In a regular time trial, he was probably underwhelming. In a short race of a few hundred yards, he was your man.

It’s how Redlands Classic officials set it up in 1998. Armed with a myriad of world-class road racers at the 14th annual Redlands cycling clash, Bairos landed on a Sunshine Germany team.

Organizers set it up on State Street.

In a week dominated by U.S. Postal’s Jonathan Vaughters, who was chased throughout the weekend by future Tour de France champion Cadel Evans, along with team duels set up with Navigators, Volvo-Cannondale and Team Shaklee.

The 20-year-old Bairos out-quicked all comers in that opening street sprint. Bairos, for his part, was trying to claim a spot in the 2000 Olympic Games. A couple years later, I had a chance to chat with him for a story on his destination for Sydney, Australia.

Bairos was a track sprinting sensation, officially named to the U.S. Olympic cycling team by a female United States Cycling Federation official. The Redlands original, who found out he was on the team, had to pass a 45-minute physical by USCF doctor Gloria Beim on July 22, 2000.

The 20-year-old Bairos out-quicked all comers in the opening street sprint.

Bairos, for his part, was trying to claim a spot in the 2000 Olympic Games.

A couple years later, I had a chance to chat with him for a story on his destination for Sydney, Australia.

He was a track sprinting sensation, officially named to the U.S. Olympic cycling team by a female United States Cycling Federation official.

“I’ve gone the entire emotional spectrum,” Bairos said. “On both sides. This is so much more of a relief to hear her say it. I couldn’t be happier.”

Bairos, who found out he was on the team, had to pass a 45-minute physical by USCF doctor Gloria Beim on July 22, 2000. She flew from Colorado to examine Bairos, who was just shaking off the effects of a near-fatal crash while competing in the World Cup Cycling Championships at Mexico City on June 17.

Beim put Bairos through a virtual torture test, ranging from sprints, starts, riding, plus examining his knee and the rest of his body.

“I think she was extremely surprised to see how well I was doing,” Bairos said. “She saw the force in my starts, the strength in my legs, and the only thing that was wrong was there was a little infection in my knee.”

She flew from Colorado to examine Bairos, who was just shaking off the effects of a near-fatal crash while competing in the World Cup Cycling Championships at Mexico City on June 17.

“I’ve gone the entire emotional spectrum,” Bairos said. “On both sides. This is so much more of a relief to hear her say it. I couldn’t be happier.”

Beim put Bairos through a virtual torture test, ranging from sprints, starts, riding, plus examining his knee and the rest of his body.

“I think she was extremely surprised to see how well I was doing,” Bairos said. “She saw the force in my starts, the strength in my legs, and the only thing that was wrong was there was a little infection in my knee.”

THE CRASH, FALL IN MEXICO

Bairos, the Redlands entry, was sailing along in perfect health and a lock for an Olympics berth before the disastrous fall during the Keirin portion – brakeless fixed-gear cycles – of the World Cup in which he went more than 20 feet over the track railing.

The torturous numbers – a 25-foot fall, seven days in the hospital, a non-finished 750-meter race.

“As soon as I went over the rail, I knew I was in trouble,” Bairos said after returning to the Inland Empire. “I just closed my eyes and prayed.”

During the race, a Venezuelan rider pushed his way to the front, forcing a French rider to react so he wouldn’t fall. They got tangled up and a Swiss rider behind Bairos hit his rear wheel, causing the chain-reaction crash.

Results were devastating.

A shattered right sinus cavity. A fractured left sinus cavity. A gash on his chin. Black eyes. Missing teeth. A broken jaw. Cuts, bruises and contusions all over his body. Doctors had to wire his jaw shut so his face could heal. Two screws were placed in his kneecap.

A little over two years earlier, he’d been celebrating a 200-yard downtown sprint win over guys like Vaughters, Evans, Trent Klasna, Chris Horner and a bunch more at Redlands.

In chasing Sydney’s Olympics, Bairos had surgery in Mexico then was transported to Loma Linda University Medical Center, where he had additional surgery.

“I learned that I never count my chickens before they’re hatched,” said Bairos.

In August, he said, “I’m not quite 100 percent. But I’m extremely close. Once it gets time to race, it’s not a question of being 100 percent. It’s a question of being 110 percent, 120 percent, 130 percent.”

ONE SECOND AWAY FROM QUALIFYING

Bairos had been regarded as the United States’ best cycling starter from a standing or stop position. He will lead off in the newly added sprint event, followed by longtime teammate and friend Marcelo Arrue, then by track veteran Jonas Carney.

“Nobody can go 200 meters from a stop position like Johnny can,” Redlands Bicycle Classic official Craig Kundig said. “That’s what he does, and he’s the best in the country. That’s why they have him leading off.”

There was no question in the minds of USCF officials that Bairos was the best man for the ride, so when the organization named the Olympic team in early July, it held open a spot for him until a deadline for submitting the roster. There was no medalist.

“It was whether I was healthy enough to fill the spot,” Bairos shared. And after passing the physical, it’s on to Sydney.

*****

Bairos won a gold medal in the 1999 Pan American Games at Winnipeg, Manitoba – a Canada stop. He had three top-four finishes in World Cup competition and five top-10 finishes in national events.

“It’s usually dominated by the French, but the Spanish team has been giving them a tough time the last nine months,” he noted. “There’s a big gap between them and everybody else.”

At Winnipeg, Bairos didn’t let his USA side down among a dozen on-track events. Between USA teammates, Arrue and Marty Nothstein, that trio racked up 47.19 seconds in their triple threat duel against the other teams.

Those USA teams had plenty of hopes of contending at least for a bronze medal. Arrue, Bairos and Nothstein edged Cuba for the win, taking home a gold medal. Argentina grabbed the bronze.

Bairos’ clairvoyance paid off: Eventually, the USA held its way up.