A Redlands Connection is a concoction of sports memories emanating from a city that once numbered less than 20,000 people. From pro football’s Super Bowl to baseball’s World Series, from dynamic soccer’s World Cup to golf’s and tennis’ U.S. Open, major auto racing, plus NCAA Final Four connections, Tour de France cycling, more major tennis like Wimbledon, tiny connections to that NBA and a little NHL, major college football, Kentucky Derby, aquatics and Olympic Games, that sparkling little city sits around halfway between Los Angeles and Palm Springs on Interstate 10. Among this city’s top tennis connections, this might be one of its best ever. – Obrey Brown

I WISHED THERE WERE more guys like Darrell Hudlow.

Redlands, that city where football turned out highly successful, soccer and softball became high-level sports, throw in some impressive swimming, above-average baseball, plus amazing track & field and golf connection off the charts, figure this: There was an original Mr. Tennis in this city.

It might’ve been Hudlow.

In a low-populated city that’s produced multitudes of high school and collegiate tennis champions, including some Wimbledon and U.S. Open connections, Hudlow comes quickly to mind.

I wasn’t even aware he played tennis, not at first. There was a place to go dancing, said once-young lovers. Hudlow had a drive-in, located on “the highway to Redlands.”

Hudlow was proprietor of a big place near downtown. Upon moving to Redlands in 1979, I couldn’t miss the greenish sign out there on a Redlands Blvd. building — where the Bank of America now sits, I think.

Hudlow was a University of Redlands Hall of Famer. It was stressed to me likely by my City Editor, Dick West, of the Redlands Daily Facts – that Hudlow had been a tennis player. A damned good one at that.

Immense Bulldog tennis coach Jim Verdieck may well be that school’s top name associated with championship brilliance around Redlands. Hudlow showed up on that scene long before Verdieck built his dynasty.

Verdieck’s teams won an unheard-of 921 tennis duals over a 38-year span. In 35 of those years, Redlands copped a conference championship. There were plenty of top players, namely Verdieck’s sons, Doug and Randy, among other brilliant players wearing those maroon and grey uniforms.

Long before the Borhnstedt and Verdieck brothers started playing at that local high school — they played at both Wimbledon and U.S. Opens — Hudlow had long set an early tone for high level tennis in Redlands.

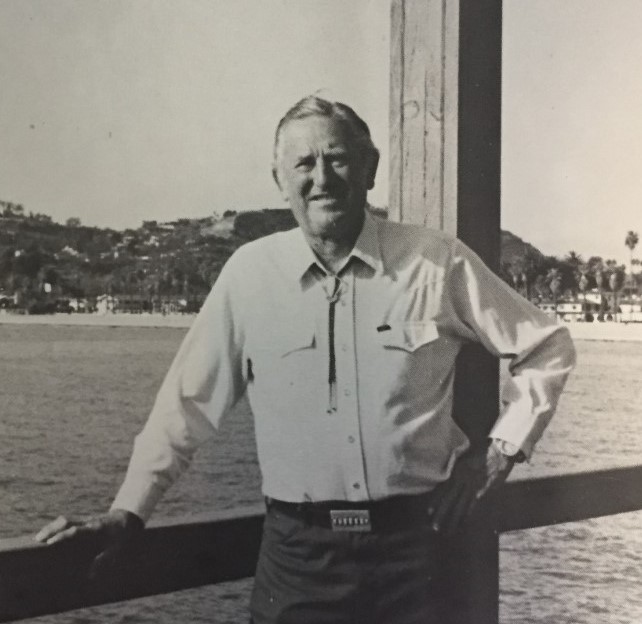

Hudlow’s, incidentally, is a now-disappeared liquor store over on that Redlands Boulevard site. He just laughed. “I went into the liquor business,” he cracked. “I quit tennis because I didn’t have time to play any more.”

That liquor business, at least in Redlands, was taboo amidst his college campus during those days touching 1940s and 1950s. “The university fought me,” said Hudlow, who carried a grudge against his alma mater for years. “It was a staid old school. You couldn’t even dance up there.

“Anyway, they took this liquor thing to the city council.”

Hudlow won when that university turned over a new leaf, he told me. When that school inducted him into its relatively new Hall of Fame in 1984, they extended a familiar hand. “The university,” he said, sarcastically a few days before the event, “is having a cocktail hour before the (Hall of Fame) dinner.”

Maybe, I told him, he ought to provide liquor. “If I did that back when I was going to the university,” he said, chuckling, “I’d have gotten kicked out of school.”

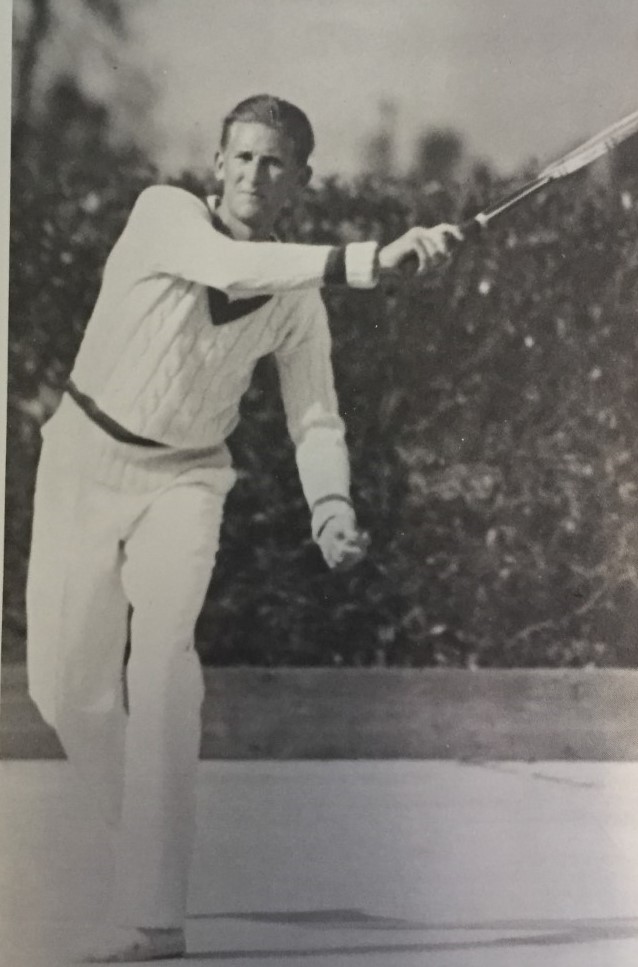

UofR tennis had long been a dominant program. Hudlow was conference singles champion from 1937-39.

It was curious timing. Verdieck, who hailed from nearby Colton, was playing football for a dynamic group called the Vow Boys up in Palo Alto. Stanford University had vowed that it would never lose to USC. Following a football loss to USC in 1932, Stanford players vowed they would never again lost to the Trojans.

Hudlow, for his part, was playing championship-level tennis while Verdieck was making football his college-playing mission. Hudlow won amateur singles titles in Arizona, Michigan and Arkansas. Verdieck was Rose Bowl dominant.

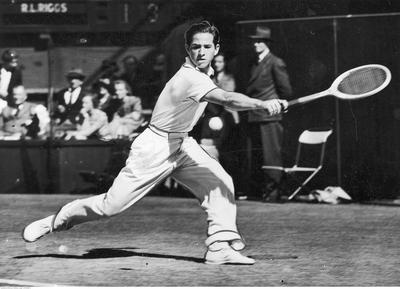

Some of Hudlow’s opponents were Frank Kovacs, a Wimbledon champion who later lost to legendary Bobby Riggs in the 1941 U.S. Tennis Championship finals.

Hudlow also played Gardner Mulloy, the four-time U.S. Tennis Champion, paired with William Talbert in doubles. Then there was Welby Van Horn, who lost to Riggs in that 1939 U.S. Tennis Championship finals. Hudlow beat Van Horn at a tournament in Ojai, Calif.

Another big name Hudlow opponent was Frankie Parker, a onetime U.S. tennis champion.

Said Hudlow: “I played Jack Kramer in an exhibition in the (Redlands) university gym,” he said, “to raise money so I could go back east. I think we played to a tie that night.”

Kramer, who would become a huge tennis executive in years ahead, was a U.S. Open and Wimbledon champion.

“I can’t remember if I ever played Bobby Riggs,” said Hudlow. “I knew him. You know, on rainy days at country clubs, all people do is sit in the clubhouse playing poker. I held Bobby’s one-dollar bills for him.”

In that second class of UofR Hall of Famer selections, the original Hall headliners had to be Verdieck himself, along with football coach Frank Serrao. Lee Fulmer (baseball, basketball), John Fawcett (cross country, football and track), Charles Gillett (football), Lee Johnson (track), faculty member S. Guy Jones, track’s Samuel Kirk, Donald Kitch (football, basketball), Sanford McGilbra (football, basketball, baseball), Robert Pazder (football, basketball, baseball), football and tennis star Randy Verdieck were right there.

While Hudlow was inducted, so, too, was his coach, Lynn Jones, running those Bulldogs from 1928 through 1944. There was a lengthy list of names, likely trying to catch up with a near century’s worth of athletes and other sports-related contributors that needed enshrinement.

Hudlow, who died on June 19, 1998, said he didn’t play tennis for nearly 40 years before he sold his liquor store. When he decided to return, he played recreationally.

“I could tell you lots of stories,” he said, chuckling. “I think I’ll hold off for awhile.”

Thing is, the two of us never came back into connection.