This is part of a series of mini-Redlands Connections. This is part of a series of quick visits. Magic Johnson and John Wooden showed up at the University of Redlands as part of its Convocation Series. Future NFL Hall of Fame coach, Tom Flores, onetime NBA player John Block, legendary high school coach Willie West showed up. There are others. Cazzie Russell, for instance, came to Redlands with an NCAA Division III basketball team from Savannah, Ga. Russell, out of Michigan, was that No. 1 NBA’s overall draft pick by the New York Knicks in 1966. Today’s feature: Former Chicago Cubs’ pitcher Ferguson Jenkins.

Here’s where being a media member has its advantages:

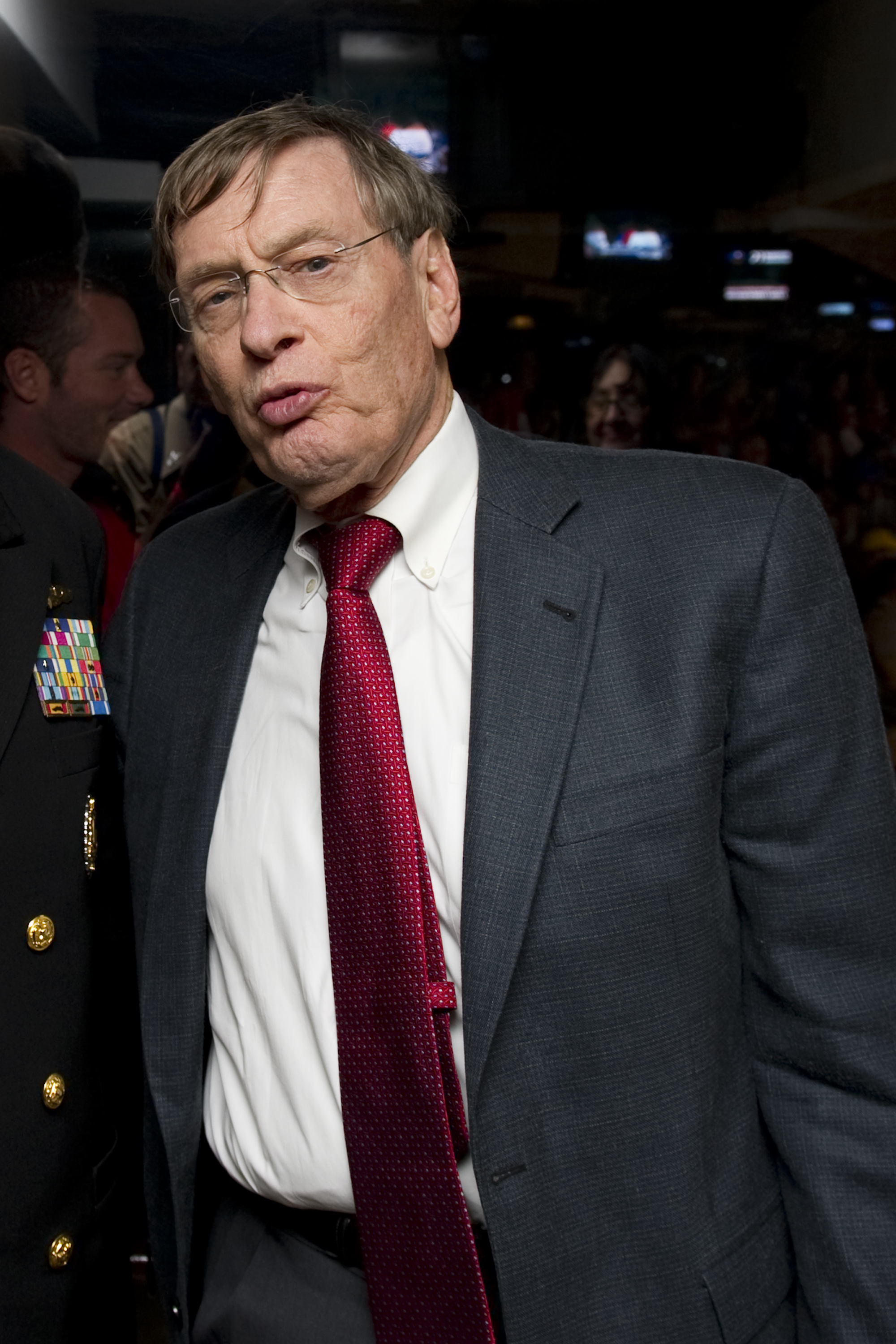

Hall of Fame pitcher Ferguson Jenkins had appeared in Redlands to help conduct a youth clinic at Community Field and, perhaps, sign a few autographs.

Chicago Cubs’ fans were plentiful throughout this nation. One notable such fan, a veterinarian who lived in Redlands, could recite all Cubs’ doctrine from those Jenkins years.

Here are guys that fans instantly thought about when recalling those Cubs’ teams from that 1960s showdown: Ron Santo, Billy Williams and Ernie Banks were headliners. Jenkins, of course, was their ace pitcher. Leo Durocher was Cubs’ manager, a fact that wasn’t enthusiastically accepted by the local vet.

“Durocher ruined Jenkins’ career,” said Redlands’ area vet. “He used him too much. Ruined his arm.”

He was adamant. So was another group of Cubs’ fans, folks that meant at least once a month at local restaurants, to chat about that Chicago team. That area vet wasn’t part of that group. Cubs’ fans were almost anywhere.

Hall of Fame pitcher Ferguson Jenkins spent a few hours in Redlands, teaching baseball to youths and answering questions about former manager Leo Durocher (photo by Wikipedia).This gathering Redlands Community Field, of course, was years later — after baseball had starting dedicating a full core of relief pitchers to save games. In Jenkins’ days, legendary pitchers like Bob Gibson, Juan Marichal, Mickey Lolich, Don Drysdale, Tom Seaver, Jim Palmer, Catfish Hunter, Vida Blue, you name it, would pitch 300-plus innings each year.

Bullpens weren’t quite as deep. So here was Jenkins in my sight line: “Tell me about Leo Durocher.” Jenkins took it from there.

“Leo helped make my career. If it weren’t for him … I’ll tell you, he taught me a lot. I owe him a lot. I owe a lot of my career to him.”

Under Durocher, Jenkins became one of baseball’s top hurlers. To pick him up, Chicago sent veteran pitchers Bob Buhl and Larry Jackson to Philadelphia as part of that deal.

“When I got traded to the Cubs,” he said, referring to that 1966 deal in which Philadelphia traded away a future Hall of Famer to those Cubs, “we were the worst team in baseball.”

Durocher had just been named Cubs’ manager. Jenkins, under Durocher, won 20 games over six straight seasons — all seasons that Durocher had managed him, incidentally.

“He worked you, no question about that,” said Jenkins.

The Cubs never won a pennant, a division championship, or made it to the World Series during those Durocher and Jenkins days.

“Some of those years we came to spring training,” said Jenkins, “and we knew we’d have a chance to win … because of Leo. He turned that team around in Chicago.”

Where was that veteran, that so-called Cubs’ fan? He needed to be listening to all this.

Durocher, who’d been teammates with Ruth & Gehrig, turned Brooklyn into pennant winners, managed Jackie Robinson and Willie Mays, among others, Durocher was, perhaps, baseball’s greatest connection to multiple generations.

“I never had any trouble with Leo — never,” said Jenkins. “I know what people say about him, what they try to insinuate.”

If there was a criticism of Durocher from that 1969 season, said Jenkins, “it’s probably that he never gave our regular guys a break.”

It was Don Kessinger, Glenn Beckert, Billy Williams, Ron Santo, Ernie Banks, Jim Hickman, Randy Hundley and Don Young. The Cubs took second to the Miracle Mets.

That season, 1969, Jenkins finished 21-15 with a 3.21 ERA over 311 1/3 innings.

I still have no idea how someone from Redlands had lured that fabulous Jenkins — 284-226 over 19 seasons — to Community Field in 1994. In reality, it was Redlands Baseball For Youth President Steve Chapman, a die-hard Cubs’ fan, who sent a white limousine to bring Jenkins to that ballpark.

It was almost an afterthought that Julio Cruz, a onetime Redlands High player, and Rudy Law, a former Dodger and White Sox player, also showed up. Infield play, outfield play, a little hitting — plus pitching.

Ex-Pirates’ pitcher Dock Ellis was also present. Ellis, it’s likely remembered, is the pitcher who surrendered a tape measure home run hit by Reggie Jackson out of Tiger Stadium at the 1971 All-Star game.

Jenkins, incidentally, was one of just four N.L. pitchers in that 6-4 loss to the A.L. Giants’ pitcher Juan Marichal pitched in his final mid-summer classic and so did Houston’s Don Wilson.

Imagine, two of that year’s four N.L. all-star pitchers — Ellis and Jenkins — had shown up in Redlands a couple decades later. Jenkins arrived at Community Field in that white limo. Dressed in his Cubs’ uniform. Showed kids his style of pitching.

“Show ’em your wallet,” he said, demonstrating his high-leg kick, twisting his torso with his left buttock toward the hitter, “and let it fly.”

That’s how a Hall of Famer did it.

Fans might not remember this, Jenkins said, “but Leo converted me into a starting pitcher. I’d been a reliever. He turned my career around. I became a Hall of Famer.”

Jenkins left Redlands like he’d arrived — in that white limo.