Redlands Connection is a concoction of sports memories emanating from a city that once numbered less than 20,000 people. From the Super Bowl to the World Series, from the World Cup to golf’s U.S. Open and the Olympics, plus NCAA Final Four connections, NASCAR, the Kentucky Derby and Indianapolis 500, Tour de France cycling, major tennis, NBA and a little NHL, aquatics and more, the sparkling San Bernardino County city that sits around halfway between Los Angeles and Palm Springs on Interstate 10 has its share of sports connections. – Obrey Brown

In memory of the 1973 World Series:

Dee Fondy, an ex-major league baseball player who lived in Redlands for years, never seemed to show up in the spotlight. He was completely without fanfare. For an ex-big league ballplayer with some real time in the spotlight, Fondy preferred to keep his collar up and the brim of his hat down.

His son, Jon Fondy, said his late father never sought the publicity of local newspapers, preferring a low-key existence. A war hero and a local product (though he was born in Texas) from San Bernardino, Fondy was a golf-playing member at Redlands Country Club during his retirement years.

It wasn’t all that well-known, however, that Fondy was a premiere advance scout for the New York Mets — a spot that is most likely among baseball’s under-appreciated roles. A year after producing a scouting report that nearly helped the Mets win the 1973 World Series, Fondy landed a spot with the Milwaukee Brewers.

It was Fondy who scouted the defending champion Oakland A’s for the Mets in its 1973 showdown against a Hall of Fame-led team, namely Reggie Jackson, Rollie Fingers, “Catfish” Hunter, not to mention a well-traveled manager Dick Williams.

The Mets, injured and suffering throughout the season, managed to package an 83-79 season together. It was good enough to win the National League Eastern Division.

In the National League playoffs, New York outlasted a 99-win Reds’ teams loaded with Hall of Famers — Joe Morgan, Johnny Bench, manager Sparky Anderson, Tony Perez, plus Cooperstown’s overlooked non-inductee Pete Rose — in five games.

The A’s were baseball’s defending champions, having beaten the Reds in the 1972 World Series. This time, it was Oakland taking on the Mets, whose Hall of Fame talent included future Hall of Famers Tom Seaver, Yogi Berra and Willie Mays, who was playing his final season.

The Mets had a 3-2 lead in the Series, based off 10-7, 6-1 and 2-0 wins over the A’s in Games 2, 4 and 5. Hunter outdueled Seaver in Game 6, 3-1, before Kenny Holtzman beat Jon Matlack in Game 7, 5-2, for Oakland’s second straight World Series title.

Fingers, the loser in Game 3, saved three of those A’s wins. It took Oakland’s best efforts.

“Dad’s scouting report was in Yogi Berra’s back pocket,” said Jon Fondy, Dee’s son, who had produced the report. “They almost pulled it off and beat the A’s.”

Berra, a Hall of Famer, was New York’s manager. Part of Fondy’s scouting report had to be data that led to Mets’ pitchers holding A’s hitters to a .212 Series average with just two home runs.

The comparative rosters of both teams should have left Oakland in position to sweep the Mets, or at least take them in five games. Fondy’s notes on the A’s, however, gave New York’s pitchers a strong advantage.

One season later, Fondy was off to Milwaukee to join the Brewers.

Fondy, a lefty during his playing days, wound up with the young, expansionist Brewers – eventually heading a scouting department that signed Robin Yount and Paul Molitor. In the Brewers’ only World Series appearance, 1982, those future Hall of Famers were paramount in the teams’ success.

CONSTRUCTING AN OBITUARY

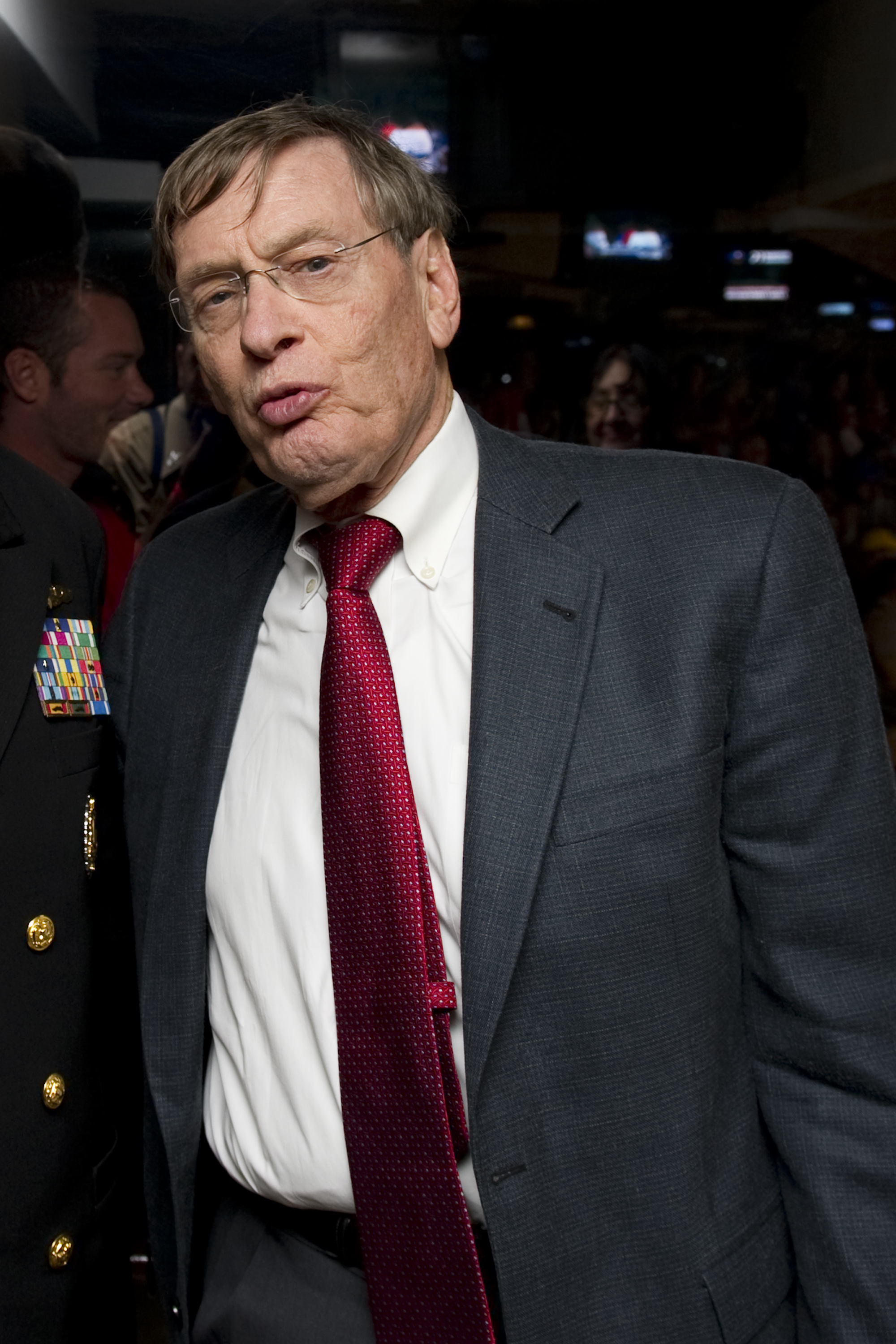

Upon Fondy’s death – Commissioner Bud Selig responded to a call from a local newspaper – to laud the career and life of the onetime Pirate, Cub and Red first baseman. Fondy had once been traded with Chuck Connors, who went on to fame as television’s “The Rifleman,” a CBS production.

Selig, of course, knew Fondy from his days as Brewers’ owner. Fondy worked for Selig.

In August 1999, Dee Fondy died at a retirement home in Redlands.

In his obituary, I wrote: “He played for the Pittsburgh Pirates, Chicago Cubs and Cincinnati Reds and was the last player to bat in Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. Died of cancer. He was 74.

In the obit: “Fondy, who was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer a year earlier, died at Plymouth Village.”

His death reverberated through baseball. He was well known.

While working on Fondy’s obituary, I placed a call to the MLB offices in New York City, seeking comment — a standard procedure. Baseball usually responded quickly. In this case, it was the commissioner, Bud Selig, who placed the return call.

I was out of the office when Selig returned the call. Mike Brown, the news editor (no relation), took the call, jotted down Selig’s comments, and forwarded them to me. I must’ve missed the commissioner’s call by just minutes on that August day.

“Dee Fondy was one of my favorite people,” Selig told Mike Brown. “He had a great sense of humor. He and I used to kid each other a lot.”

FONDY’S MAJOR LEAGUE CAREER 1951-58

Fondy hit .286 with exactly 1,000 hits (69 HRs) over eight seasons in the majors, having batted .300 in four of those seasons. His debut, in April 1951, came just a month before Willie Mays’ legendary MLB entry.

Signed originally by the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1946, Fondy came to spring training in 1949 and competed with Gil Hodges and Connors for the starting job at first base. Dodger lore shows, of course, that Hodges prevailed to win that notable spot.

A side note, of course, is that Hodges was the managerial architect of that 1973 Mets’ team. Hodges died just before the 1972 and was replaced by Berra.

Fondy played in the Dodgers’ farm system until being traded, along with Connors, to the Cubs for outfielder Hank Edwards. It was a golden era of Dodger baseball that included Hall of Famers Jackie Robinson, Duke Snider, Roy Campanella, plus Hodges, Pee Wee Reese and a host of other highly popular Dodger players.

Fondy won a spot on the Cubs. His first major-league hit was a bases-loaded triple off St. Louis pitcher Ken Raffsenberger on opening day, April 17, 1951, at Wrigley Field.

Eventually, Chicago traded Fondy to Pittsburgh in 1957. In that deal, the Cubs sent Gene Baker and Fondy for the Pirates’ Dale Long and Lee Walls. Midway through that ’57 season, Fondy was leading the National League with a .365 average, eventually finishing at .313.

Traded to Cincinnati for slugger Ted Kluszewski, a transaction mentioned by Tom Cruise’s character in the 1988 movie “Rainman,” Fondy’s career concluded in that 1958 season.

In a remarkable twist of baseball trivia, it was Fondy who grounded out for the last out at Ebbets Field in Pittsburgh’s 2-0 loss to the Dodgers on Sept. 24, 1957. That grounder went to Don Zimmer, whose throw to first baseman Jim Gentile ended an era.

The Dodgers moved to Los Angeles the following year.

Jon Fondy had some fun memories.

“I ran into Willie Mays once and he said, ‘I’ve still got the bruises from the tags your dad used to give me. He was a hard-nosed player,’ ” said Jon, a freelance cameraman who has covered major league games.

It was off to work, eventually, as a scout for the Mets and in Milwaukee, where he signed Molitor, who went on to a Hall of Fame career. Upon Fondy’s arrival, the Brewers took off to becoming a top-flight American League team that reached the World Series in 1982.

Fondy retired from baseball in 1995 after serving as a special assistant to the Milwaukee general manager.

“He was as good a judge of talent as I’ve ever known,” Selig told Mike Brown. “He played a great role in the development of the Brewers. I had as much faith in his baseball knowledge as anyone I know.’”

FONDY’S FUNERAL: ONE FINAL HURRAH

It was at Fondy’s funeral that several ex-players – Ray Boone and onetime Oakland A’s third baseman Sal Bando included – had shown up to pay final respects. Another funeral-goer was a man named Fred Long. For years, Long coached local baseball, eventually rising to becoming a major league baseball scout.

Fondy’s influence had been felt in Long’s scouting life.

Long, who was nearing 80 at the time of Fondy’s funeral, had plenty of stories to share, sporting a World Series ring — Florida Marlins, 1997.

Fondy, said Long, was one of the best guys he’d ever known. “And the guy knew baseball, too. You should’ve heard him.”

His minor league career included stops at Santa Barbara (California League), Fort Worth (Texas League) and Mobile (Southern League), each a Brooklyn Dodger farm club.

Before his climb into the major leagues, Fondy racked up 863 minor league hits, whacking out 130 doubles and 52 triples.

His career as a minor leaguer, major leaguer, scout and scouting director covered 1946 through 1995.

Isn’t it interesting that Fondy worked as a scout for the same Mets’ organization in which Hodges — who edged him for Brooklyn’s first base job — was the manager?

Born on Halloween in 1924, Dee Virgil Fondy’s death took place on Aug. 19, 1999 in Redlands. Fondy, a native of Slaton, Texas, served in the Army during World War II and was part of the forces that landed on Utah Beach in Normandy in 1944, three months after D-Day. He received the Purple Heart.

Fondy had also been survived by twins, Jon Fondy and Jan Cornell of Las Vegas. His wife, Jacquelyn, had died a year earlier. Fondy’s funeral was in nearby San Bernardino, almost directly next door to Perris Hill Park’s Fiscalini Field.

Growing up in San Bernardino, Fiscalini Park was where Fondy played plenty of baseball.