This is part of a series of mini-Redlands Connections. This is Part 3 of the series, Quick Visits. Magic Johnson and John Wooden showed up at the University of Redlands as part of a Convocation Series. This piece on Tom Flores was another one. Hall of Fame pitcher Ferguson Jenkins, former NBA player John Block, legendary high school coach Willie West showed up. There are others. Cazzie Russell, for instance, came to Redlands with an NCAA Division III basketball team from Savannah, Ga. Russell, out of Michigan, was the NBA’s overall No. 1 draft pick by the New York Knicks in 1966.

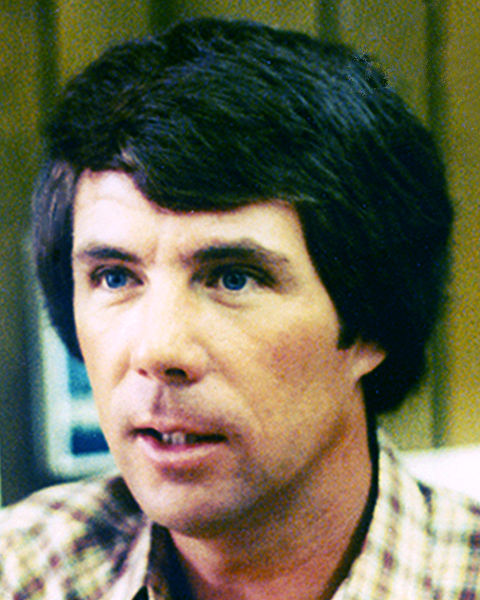

Today’s feature: World-class distance runner Steve Scott.

Steve Scott could’ve wiped out the field at the 2001 version of A Run Through Redlands.

Think about it.

There were 136 times in his career that Scott ran the mile in four minutes, or better. He held the American record in that distance for a quarter-century. His place in track & field’s history books are cemented forever.

That he showed up to run in Redlands was incredible. He wasn’t there to compete, though.

“I’ve got friends here,” he said, standing in front of a crowd of local runners. “I ran with them in the 5K … but I didn’t enter the race. This was just a fun run for me.”

It must’ve never occurred to runners on that Sunday morning that they were running next to a legend.

It occurred to me, however, that I had a genuine story on my hands.

I gigged the local newspaper photographer, Lee Calkins, to get Scott’s photo. Scott, charming as he was spectacular, had given me his telephone number for, perhaps, a future feature article. I could hardly wait.

INTERVIEW WITH A LEGEND

Talk centered around that remarkable record of sub-four-minute miles. He was a legitimate superstar on the track – nationally and internationally.

He was just 22 when Britain’s Sebastian Coe set the world mile record (3:48.95) in Oslo, Sweden in 1979. Running second that day was none other than Scott, the miler from Upland. Eventually, his lifetime best over one mile was 3:47.69.

It seems almost sub-human to recognize his lifetime best in the 800 was 1:45.05.

Olympics?

Like many athletes in 1980, ready to erupt at the Games, he was part of a U.S. contingent that wasn’t allowed to attend the Moscow Olympics because America boycotted.

“I won (the 1500) at the Olympic Trials,” he told me. “I was ready for the Olympics, believe me.”

Scott did win the gold medal at the Liberty Games, an event organized to allow boycotting nations to enter their athletes. Held in Philadelphia, Scott held off Sudan’s Omer Khalefa by a fraction of a second in 3:40.19 over 1500 meters.

In the 1984 L.A. Games, Scott ran 10th in the 1500; fifth at the 1988 Seoul Olympics.

Only one of his lifetime bests – 800, 1000, 1500, mile, 3000 or 5000 – was run on American soil. In the 5000-meter, Scott ran a 13:30.39 at legendary Hayward Field in Eugene, Ore.

“Running in Europe is great,” he said. “There’s nothing like it. Track is huge over there. You can really make some money.”

Appearance fees, purses, shoe sponsorships, bonuses for world records – “the big money is overseas,” said Scott. “There’s no big money in American track.”

Holder of the American one-mile record on three different occasions – becoming the first American to crack 3:50, incidentally – Scott set the American record (3:47.69) in July 1982.

When I spoke with Scott in 2001, he still held the American record in the mile (his record was broken in 2007 by Alan Webb, 3:46.91).

“I love road racing,” he said. “It doesn’t matter to me whether the race is on the track, indoor, outdoor, on the roads.”

I used to cover the Sunkist Invitational in Los Angeles, a pre-season indoor meet, when Redlands would send athletes. I wasn’t around when Scott ran his first mile under four minutes in 1977.

He raced against the likes of Sydney Maree, Ovett, Coe, Steve Cram – legendary figures over the mile distance.

Then there was the Dream Mile, he called it.

“Three of us,” Scott said, referring to New Zealand’s John Walker and Ireland’s Ray Flynn, “all ran under 3:50.”

It took place in Oslo, Norway in 1982. Scott won in 3:47.69, Walker was next in 3:49.08 and Flynn was third in 3:49.77.

“Whew,” Scott recalled. “I can’t remember a bigger race with that much speed.”

Walker’s run is still a national mark in New Zealand. So is Flynn’s mark in Ireland. Twenty-five years later, Webb cracked Scott’s record.

For Scott, it all started in high school. Who could have foreseen the moment that Scott would race against Walker, who logged 135 races under four minutes?

“I ran cross country at Upland High School,” he said. “There was a coach there who kept after me to run track.”

In the 1972 Olympics, a U.S. runner, Dave Wottle, had won the gold medal in the 800. Scott watched, then developed a strong desire to run track. In college at UC Irvine, Scott was NCAA Division 1 champion in the 1500.

“My times in high school were nothing special,” he said, referring to 1:58 in the 800 and 4:30 in the 1500.

“Running those (record) times in the mile, holding the record,” he said, “was the most special part of my career. Those were great feelings.”

COULD’VE WIPED OUT REDLANDS RACE

As for that 2001 Redlands’ 5K, consider that he once ran 5,000 meters in just over 13 minutes. In 2001, I seem recall the course record at just over 15 minutes – virtually a sprint.

Scott’s background produced a mark that was two minutes quicker.

What shouldn’t go unnoticed here is that A Run Through Redlands organizers, dating back to its origins in the early 1980s, couldn’t conceive they could offer up a significant event that a world figure might show up to run — even if it was a “fun run.”

Could he have wiped out the Redlands field, I asked him?

He smiled.

“Maybe.”