A Redlands Connection is a concoction of sports memories emanating from a city that once numbered less than 20,000 people. From pro football’s Super Bowl to baseball’s World Series, from dynamic soccer’s World Cup to golf’s and tennis’ U.S. Open, major auto racing, plus NCAA Final Four connections, Tour de France cycling, more major tennis like Wimbledon, tiny connections to that NBA and a little NHL, major college football, Kentucky Derby, aquatics and Olympic Games, that sparkling little city sits around halfway between Los Angeles and Palm Springs on Interstate 10. For Pomona-Pitzer College to reach its road game against at its SCIAC rival, University of Redlands, their driver had to take that University Street exit off I-10 – Obrey Brown

There was something strangely familiar about how visiting Pomona-Pitzer College had put an end to a longtime men’s basketball domination by SCIAC rivals, especially a University of Redlands squad one night in January 1983.

For years, that small SCIAC basketball chase had been a two-team race confined between powerhouse Whittier College with Gary Smith’s coached Bulldogs usually a close second place.

Hmmm.

Around his seventh season coaching at Pomona-Pitzer, Popovich had his team headed to Minnesota as SCIAC champions, a qualifying spot in NCAA Division III playoffs. “It’s just neat to have somebody besides Whittier and Redlands win,” he said.

It took awhile.

Located consistently were two teams on different historic losing streaks — Caltech, from Pasadena, and Pomona-Pitzer College from nearby Claremont. It certainly didn’t seem like a launching pad for Popovich, en route to an NBA Hall of Fame coaching career.

Maybe it was Popovich using his bench that night in 1983. It was, believe it or not, reminiscent of UCLA a few years earlier. The Bruins, then under coach Larry Brown, had reached NCAA’s championship game against Louisville — later vacated over rules infractions.

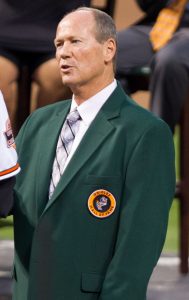

Who’d have believed that Gregg Popovich would launch an NBA Hall of Fame coaching career having started at NCAA Division III, tiny Pomona-Pitzer College in Claremont, Calif.? Part of that trek went through the University of Redlands, Whittier, Claremont-Mudd, Occidental, La Verne, plus a few others. (photo by Wikipedia).

Popovich was an assistant to Hank Egan, then at Air Force, when he took Pomona-Pitzer’s job. That first Sagehens’ team was 2-22, losing to Caltech, which had set an NCAA record with 99 straight losses.

In that 1983 game at Redlands, Kurt Herbst was Pomona-Pitzer’s big banger against the Bulldogs. Redlands couldn’t penetrate his 6-foot-6 size, a wide body who had some help that night.

Backtracking a few years later, it was Pomona-Pitzer that famously lost to Caltech, ending that then-dubbed Engineers’ 99-game losing streak. I remember that story went on Associated Press’ wire. I published that four-paragraph brief in a local newspaper.

After all, two teams in Redlands’ conference seemed mildly interesting to our readership. That was our mandate, of course, to keep our pages local.

The Sagehens, for all intents and purposes, were no more talented than a college freshman team — maybe not even that good. So when I approached Popovich about those UCLA observations, he quickly summoned me inside the Sagehens’ locker room.

He seemed excited, perhaps impressed that I’d made that wise connection.

“Yes,“ he said, “that’s exactly the blueprint we use for this team I’ve got here. Larry Brown …“ his voice drifting off into a rash of interpretation, basketball lingo and connecting the dots between UCLA and Pomona-Pitzer’s rise to prominence.

Another coincidental connection! Popovich and Brown were connected. Those connections would later surface, re-surface and surface again.

Popovich spoke of his Air Force Academy background. He’d originally met Brown at the 1972 Olympic Games tryouts – those infamous Games where Team USA lost that controversial game to Soviet Union. A handful, or so, years later, Popovich was hired at Pomona-Pitzer to coach and, along with his wife, run a campus dormitory — “something like that,” he told me.

His connection with Brown, he said while Sagehen players were giddily showering after their upset win over Redlands, dated back to those 1972 Olympic tryouts.

If Brown coached it, Popovich tried it.

“That’s the relationship we have,“ said Popovich.

At Pomona-Pitzer, Popovich was using Brown’s system of defense, not to mention a substitution pattern that was eerily similar to that of UCLA’s 1979-80 squad. Strange as it might sound, in 1983, that system stood out.

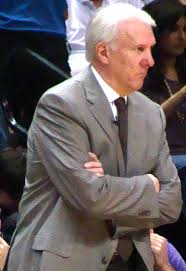

Larry Brown, coaching here at Southern Methodist University, was the catalyst to an NBA coaching Hall of Fame career for Gregg Popovich, who lifted himself from tiny Pomona-Pitzer College to the San Antonio Spurs (photo by SMU).

It was a starting five, plus two key contributors off Pomona-Pitzer’s bench.

Popovich copped to it all, via Brown. There was no possible way anything he told me that night could crystallize into Pop’s eventual NBA Hall of Fame career.

I’d keep an eye on Popovich, who took one season off to take a sabbatical at Kansas, under Brown’s guidance. By 1986, Popovich had lifted the Sagehens to the school’s first SCIAC championship in nearly seven decades — 68 years to be exact.

Trust me on this: Some Redlands folks had a few “concerns“ on just how Popovich conducted recruiting basketball players on that remarkable Pomona-Pitzer campus in Claremont.

He’d turned it around on a campus that seemed oblivious to its athletics program. Pomona-Pitzer and Caltech, I’d written, cheated its student-athletes by not offering appropriate coaching and playing facilities. Yes, academics was a shrewd leadership at those campuses. Naturally, I received negative admonitions from a few corners of that SCIAC chamber.

I’d written about how some SCIAC campuses were cheating their student-athletes — taking their tuition monies and providing them with slighted athletic facilities, inauthentic coaching and only mild support. Popovich indicated some extra incentives were plugged into his program right around this time; saying, however, he didn’t know if it was related to that column I’d published.

These campuses were supposed to stand for academic strength. Sports, it was reasoned, was pay-for-play. Intramurals. Deemed not important enough. That was my take in that piece I’d written.

Frank Ellsworth, Pomona-Pitzer’s president at the time, told me in a telephone call, protesting my writing, “I think we need to have you on our campus to explain our educational mission.“ That mission, I guess, didn’t include a shiny basketball program that included a pristine gymnasium.

I’ve got to admit, though. Within years, that campus funded itself with enough money to include high-level renovations to its entire athletic facility. That came during Ellsworth’s watch, in fact.

Truth is, many of those coaches didn’t get enough support from their administrations. Maybe they didn’t hit the recruiting trail hard enough. Popovich, in fact, did that. I didn’t report that part of it. I should have. It’s how he landed Herbst.

Little by little, Pomona-Pitzer attracted better players.

A few years later, Mike Budenholzer, a red-headed, non-scoring threat at point guard — the future NBA head coach at Atlanta and NBA champion Milwaukee Bucks, later coaching Phoenix. Hey, he was born in Arizona, showing up at Pomona-Pitzer.

Speaking of that, the article attacked a few of those SCIAC campuses: Some Redlands athletic officials were mildly upset, perhaps thinking their SCIAC rivals suspected that they’d put me up for writing that piece.

Popovich, in his own way, bailed me out.

“I think you’re one of the reasons things improved here,“ he told me on that night in 1983. Solid as they were, Popovich’s Sagehens finished a hugely impressive 6-4 record in SCIAC play, nowhere close to a conference championship. By 1986, Pomona-Pitzer won its first league title in decades — eventually fourth at NCAA Regionals.

In another nice twist, Brown — having led Kansas to an NCAA Division I championship in 1988 with Danny Manning being the key player — invited Popovich’s Division III Pomona-Pitzer team for a non-conference game the following season.

I’ll never forget the score of a Pomona-Pitzer vs. Kansas matchup at the Phog Allen Field House. It was 94-38, Jayhawks. It was Popovich’s final season, incidentally, a 7-19 record, 4-6 against SCIAC rivals, his worst season in years. Future into coaching in the NBA?

Eventually, San Antonio hired Brown, who stands today as that lone coach to win NCAA and NBA (with Detroit) championships. That Spurs’ hiring led Brown to bring on Popovich as an assistant.

Popovich went on, spending a couple seasons at Golden State, but considered that Nevada-Las Vegas’ legendary coach Jerry Tarkanian, who coached Redlands High School over 1959-61 seasons, had been railroaded out of his job with the Runnin’ Rebels.

Tark turned up, briefly, as Spurs’ coach. It didn’t last more than a half season. The guy that hired and fired both Brown and Tarkanian was former owner Red McCombs. When McCombs sold out to Peter Holt, a few years later, Popovich returned — his SCIAC connections forever bridging a gap to his NBA career.

Eventually, Popovich appeared as Spurs’ general manager. Bob Hill was their coach. All of which led to Popovich taking over as Spurs’ coach in 1996. Just over one decade earlier, he’d coached at tiny Currier Gym in Redlands, his team playing the Bulldogs.

That Popovich-to-Kansas connection was a curious relationship. Popovich tried out for Team USA during its 1972 Olympic Trials, Brown cutting him early. There was an Air Force connection.

Dean, said Popovich, and Larry “were close back in when they both coached at Air Force. Popovich got cut again when Brown was coaching that old American Basketball Association squad, Denver. That Nuggets’ coach sliced Popovich from their roster. Playing at Air Force just wasn’t good enough for a future pro, it seemed.

Connections in Popovich’s coaching world added up quickly.

I keep giving myself an “atta-boy“ for that 1983 observation on a cold, rainy night in Redlands.

*****

Speaking of basketball: Current Phoenix Suns coach Mike Budenholzer, the former Milwaukee Bucks and Atlanta Hawks coach, who has been NBA Coach of the Year, spent some time locally during his playing career at Pomona-Pitzer College – playing against both the University of Redlands and Cal State San Bernardino. It’s when the Coyotes were NCAA Division III members back in the early 1990s.

Budenholzer, who led Milwaukee to an NBA title? That redhead, seen playing point guard during his playing days at Pomona-Pitzer, took a different path into the NBA.

It was mostly on Popovich’s shoulders Budenholzer served as a San Antonio assistant coach since beginning in 1996. Popovich? By 2020? That’s when Team USA returned with an Olympic Gold Medal. In Tokyo.

Kevin Durant and Draymond Green were each part of that team. So, too, was a Popovich Spur, Keldon Johnson. Steve Kerr, an assistant that season, wrapped up another gold medal as head coach in 2024.

While Popovich took his major lift into NBA activity, longtime Pomona-Pitzer assistant Charles Katsiaficas replaced him as Sagehens’ coach, lifting Pomona-Pitzer even further into that SCIAC.

Brown? Popovich? NBA? Try this: Popovich’s Spurs knocked off Brown’s Detroit Pistons, a seven-game duel, in 2005. It was a long way from those light-achieving seasons at Pomona-Pitzer.