A Redlands Connection is a concoction of sports memories emanating from a city that once numbered less than 20,000 people. From pro football’s Super Bowl to baseball’s World Series, from dynamic soccer’s World Cup to golf’s and tennis’ U.S. Open, major auto racing, plus NCAA Final Four connections, Tour de France cycling, more major tennis like Wimbledon, tiny connections to that NBA and a little NHL, major college football, Kentucky Derby, aquatics and Olympic Games, that sparkling little city sits around halfway between Los Angeles and Palm Springs on Interstate 10. For a smallish-style city like Redlands around 1920, its connection with USA’s diligent Indianapolis is amazing. No one ever heard of an I-10 in those days. – Obrey Brown

IT WAS ALL ABOUT BUTTERMILK, or even a well-known nickname that almost everyone’s heard by now, the original “Lucky Louie.”

Louis Meyer, it seems, never even went to Redlands High. I’d searched high and low through all the Makio, Redlands High yearbooks, of that day and age. Once I’d discovered he launched a brilliant Indianapolis 500 connection, I searched for his locality. Nothing showed up. I later found out why. Meyer told me. It was simple.

“I never went to school there.”

Turns out, Louis was a summer visitor. There was a Ford auto shop just off Redlands’ downtown sector. Just opened. Nowadays, it’s Old Redlands. Real old Redlands. Edwin “Bud” Meyer, an Austrian-born eventual racer, was Louis’ older brother. He owned and operated that Model T garage. Louis, that younger brother, was where he learned to drive – not a race car, but a regular automobile.

Their dad, Edward Meyer born in France, began racing a motorcycle in 1896. Learning to drive a race car wouldn’t take much longer, Louis told me.

It was “Lucky Louie” Meyer, who drove at the 1933 Indianapolis 500, asking for a cold drink of buttermilk after winning that race. Who knew, at least that day, such a celebration would develop into one of the sport’s most identifiable moments?

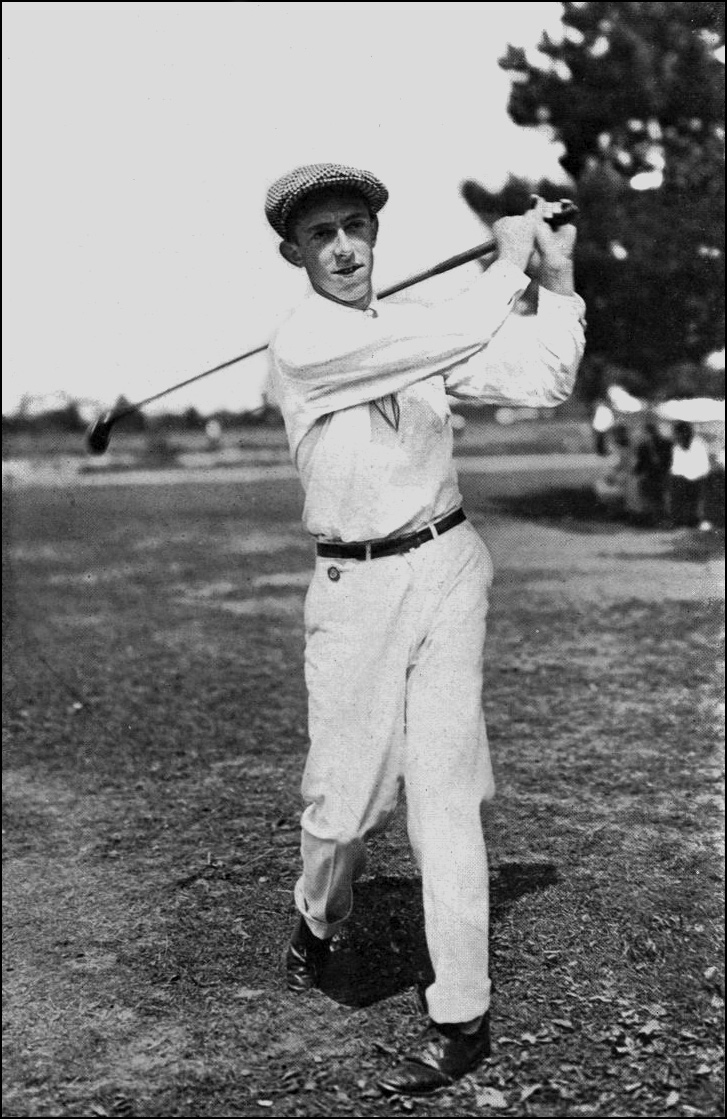

By 1926, Louis wanted to be a driver.

Louis was, said a nephew several decades afterward, was “the original Lucky Louie.” He walked away, unhurt, from crashes and various other scrapes. The family name is Meyer, and if there wasn’t a wrench, steering wheel, huge auto businesses, or some kind of speed duel going on somewhere among them, you probably had the wrong people.

Louis Meyer, a three-time winner of the Indianapolis 500 (1928, 1933 and 1936) died in Searchlight, Nev. in 1995. He got his start, learning to drive race cars from his brother, Edwin T. “Bud” Meyer way around 1920.

“There was a hill in Redlands,” recalls Terry Francis, an El Monte, Calif.-based nephew of highly famous Louis, “where (Edwin) learned to race.”

Not many years later, Louis got to Indianapolis, as a relief driver-riding mechanic in 1927, the Meyer family racing odyssey really hit the highest level.

“Wilbur Shaw got tired,” says Sonny Meyer, who was 69-years-old in 1998, a few years after Louis died. He was Lou’s son from Crawfordsville, Ind. “He was looking for someone to get in the car and drive.”

That was the story, Louis confirmed. Shaw was one of the pioneer champions at Indy. It was Shaw and Meyer.

This was the heavyweight of Louis Meyer’s race beginning at Indy. He never drove a single lap on a speedway, he told me, speeds reaching a never-before-recorded 100 mph. These days? Racers must be licensed before they’re even given a chance to make a practice run on the Brickyard track.

One year after first racing at Indy, 1928, Meyer won his first Indy 500.

“Dad had that car in second place,” said Sonny, referring to his 1927 race. “Wilbur called him in and wanted to finish the race.”

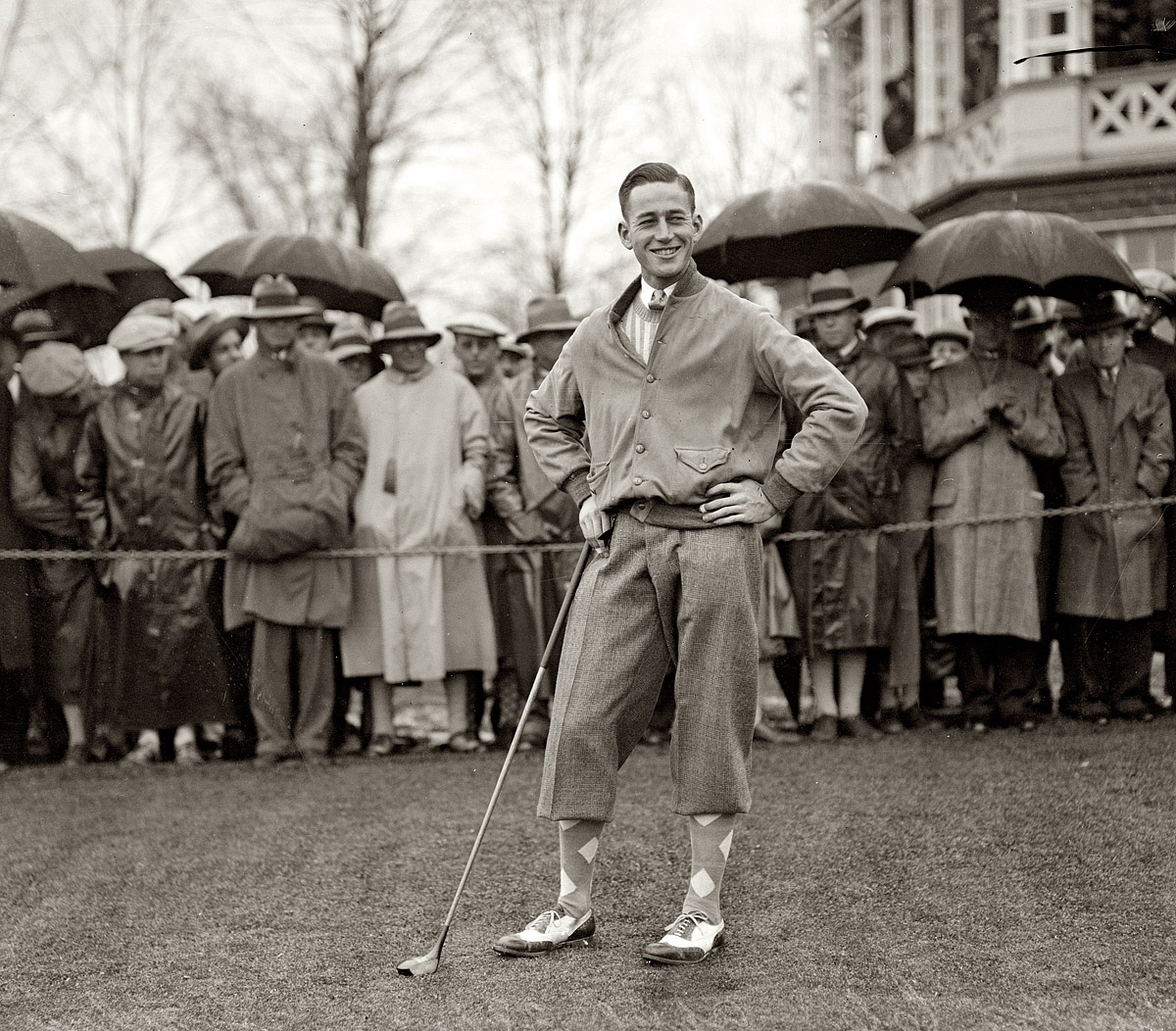

By 1927, drivers had changed from the leather-helmeted, mustachioed daredevils handling huge, ungainly machines to young jousters in low-slung bombs. Louis Meyer was a young jouster. He had never won a pole, but lined up in the front row twice. Ready to notch a few triumphs was about to veil.

MEYER STARTED INDY TRADITION

It’s no myth that Meyer was the one who started a milky tradition at Indy. Winning drivers who drink milk in Victory Lane in modern days can look back to Meyer for that one: That year was 1933.

“It was,” said Sonny, “actually buttermilk. He had a real palate for buttermilk. He told someone, ‘If I win this thing, I want you to have a cold drink of buttermilk for me after the race.’ ”

Said Francis: “The dairy council saw that and said, ‘We’ve got to jump on that.’ Louis made it a tradition at Indy.”

Historically, Meyer became the first three-time winner at Indy . In 1928, Meyer led in only 19 of those 200 laps, but that included the all-important final one at the checkered flag, notching his first 500 triumph.

Sonny recalled that his mom, June, Louis’ wife, had no hint her husband would be racing at Indy.

“She was somewhere back (in Pennsylvania),” he said. “She towed a wrecked car back to the shop. My uncle (Eddie) was racing at a track in Reading. She was there to watch that race.”

Louis Meyer chuckled over that memory. June, he said, found out he’d won that year’s Indy 500, “when the track announcer asked the crowd to give out a cheer to Eddie Meyer … the brother of the Indianapolis 500 winner.”

In 1933, Meyer recorded a three-lap victory over Shaw.

In 1936, Meyer won from the 28th starting position, tying Ray Marroun’s record for winning from the farthest back on the starting grid.

In 1939, Meyer crashed on the 198th lap, got up and walked away – literally. It was at that time that “Lucky Louie” exited racing. Famed carmaker Henry Ford made Louis a proposition, one that would bring him back to Southern California in charge of building Ford engines, including the Offenhauser.

Some numbers: He won $114,815, taking 1,916 total laps around the Brickyard track over a dozen – winning three times, second in 1929 and finishing Top 10 on six occasions.

“He always told me,” said Sonny, reflecting on that 1939 incident, “that he knew he wasn’t going to climb back into a race car.”

That, said Francis, “is why they call him Lucky Louie. All those years at Indy, the offer from Henry Ford, the crash, walking away – everything.”

Sonny? Louis’s son? Don’t let it hide that he built 15 winning Indy 500 engines.

FROM DRIVER TO ENGINE BUILDER

Louis Meyer, said Searchlight, Nev. Museum historian Jane Overy, said, “was the nicest man.” Lou died, she told me, when the city’s museum was getting set to open. He was featured prominently. Meyer had beaten the odds just to make it that far.

“There were 11 kids,” recalled Sonny Meyer. “Only three lived.”

Those kids were Eddie, the oldest, then Louis, and then, Harry, the last among those living in Southgate, Calif. “He rode with my dad,” said Sonny, referring to Harry, “as a riding mechanic (in the 1937 Indy 500).”

Meyer’s Indy-racing career concluded with that 1939 crash, which left him 12th.

Until then, the greatest engine ever raced at Indy was the “Miller,” developed by Harry Miller, Fred Offenhauser and Leo Goosen. The rights to its design were purchased by Offenhauser and the engine renamed after him. Then it was purchased by Meyer and Dale Drake and renamed the Meyer-Drake “Offie.”

It was a high-powered, specially-designed racing engine that was constantly improved over the years. Until Ford came along with its million-dollar automotive budgets and challenged for supremacy in the 1960s, Meyer had a running contract with the up-and-coming Michigan-based company.

“After he crashed (at Indy),” said Sonny, “he said he knew he wasn’t going to climb back into a race car. Henry Ford made him a proposition.”

NO REAL FUTURE IN RACING

There wasn’t much major racing around the U.S. beyond the Indianapolis 500. NASCAR had yet to see its beginnings. Louis Meyer returned to California and took part in “board” racing at places like the Rose Bowl and Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

The “season” started around Trenton, N.J., the only real race before Indy. “We’d go to Ascot (in L.A.),” recalled Sonny. “I remember because we’d have three or four drivers sleeping on our floor when we lived in Huntington Park (a Los Angeles suburb).”

Louis Meyer’s son still remembers being farmed out to neighbors, “while my mom (June) and dad went racing. During the season, they towed the race car with a rope. Mom was in the race car.”

Meanwhile, Ed Meyer still had his Redlands garage.

Sonny Meyer has a way of remembering his family’s Huntington Park address. “Dad won his first Indy 500 in 1928,” he said, “in car No. 14. That was our address: 2814 … Broadway. I still remember our phone number. It was Lafayette 8325.”

The Meyer family is more than just “connected” in racing’s history books.

Retirement was just a short drive away. For years, the Meyers had traveled to Cottonwood Cove – nine miles from a non-descript, desert community of Searchlight, Nev. It’s where Louis and June Meyer settled down for their final years.

Driving through the tiny community, located somewhere between Las Vegas and Laughlin, it became a hideaway for other celebrities, notably Hollywood’s Edith Head, early Academy Award-winning actress Clara Bow, among others.

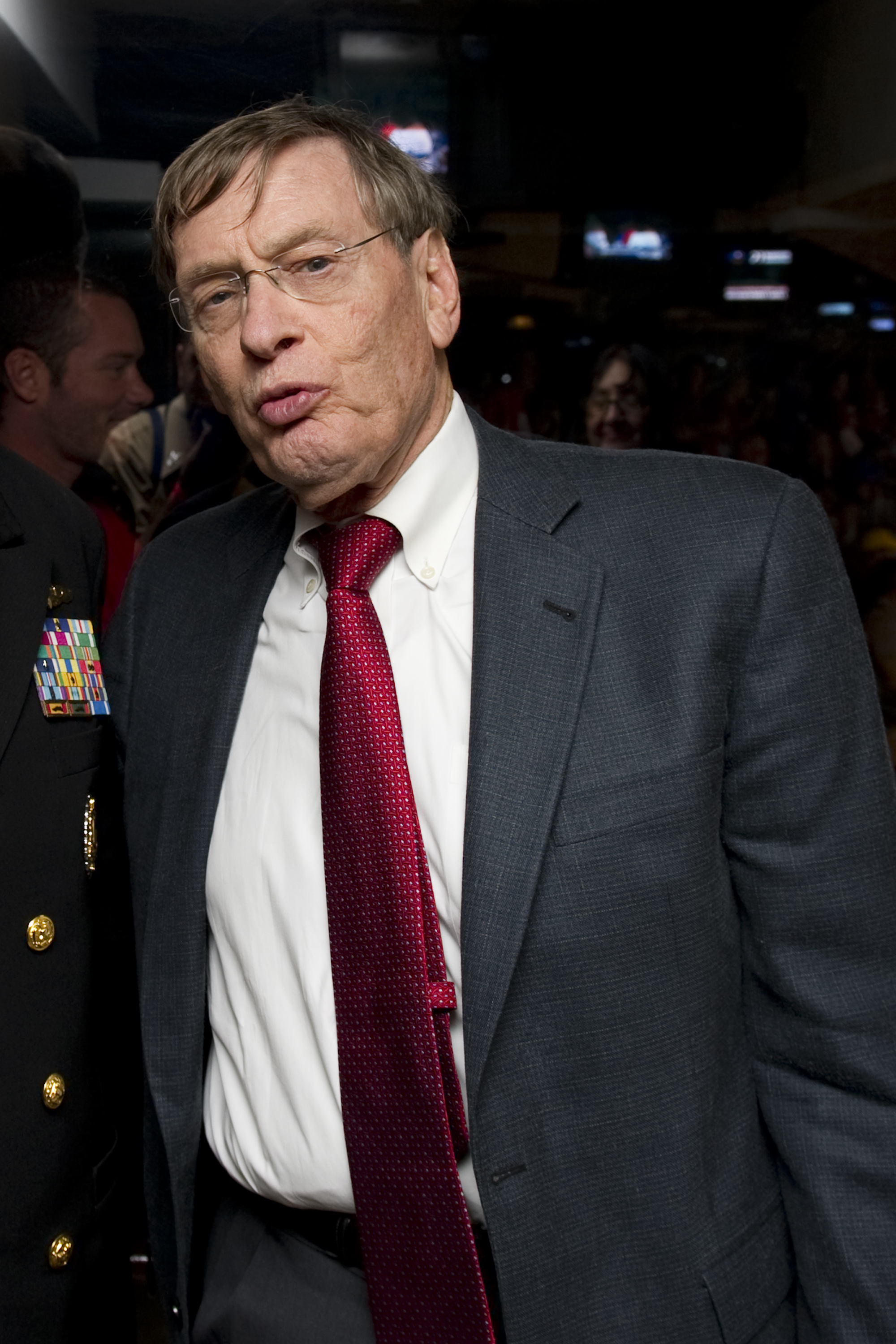

ONE FINAL CHAT WITH ‘LUCKY LOUIE’

In a very short conversation I had with Meyer in 1994, most of his Indy 500 memories had faded. Already, I’d spoken with some of his younger relatives. He’d recalled the memory of his Pennsylvania-working wife’s discovery of how he’d won the 1928 Indy 500.

Racing, said Louis, nearing age 90, “has been good to me and my family. My only regret is that time goes by so very fast.”

Truthfully, chatting with Louis didn’t last long. His elderly age was most likely the reason he decided to hang up.

Louis Meyer was born on July 21, 1904, dying on October 7, 1995. Born in lower Manhattan, New York the son of French immigrants, Meyer was raised in Los Angeles where he began automobile racing at various California tracks.

There was no track in Redlands, nor even near Redlands. Ed Meyer’s Ford shop was there, though.

Racing fans these days might not believe there were board tracks in such places as Beverly Hills, which had a 1 ¼-mile oval dubbed Beverly Hills Speedway. Or the Culver City Speedway. There was the Northern California-based Cotati Speedway in Santa Rosa. There was the mile-long Fresno Speedway and a one-mile Los Angeles Speedway in Playa del Rey.

“Yeah, Redlands,” said Francis. “That’s a key spot for the family. You never forget something like that.”

Meyer won the United States National Driving Championship in 1928, 1929 and 1933.

He died at 91, in that Searchlight community he had been living since 1972. In 1992, Meyer was inducted into the International Motorsports Hall of Fame. He was named to the National Sprint Car Hall of Fame in 1991. He was inducted in Daytona Beach, Fla.’s Motorsports Hall of Fame of America in 1993.

There was a nice little corner in Searchlight’s museum dedicated to the early racing legend.

Said the Hall of Famer, Louis Meyer: “A lot of people had me confused with the movie guy … Louis B. Mayer (of MGM). I always got a little kick out of that.”

ANOTHER ARTICLE WRITTEN by Legacy Brand, John G. Printz and Ken M. McMaken

https://legacyautosport.com/the-meyer-legacy/