A Redlands Connection is a concoction of sports memories emanating from a city that once numbered less than 20,000 people. From pro football’s Super Bowl to baseball’s World Series, from dynamic soccer’s World Cup to golf’s and tennis’ U.S. Open, major auto racing, plus NCAA Final Four connections, Tour de France cycling, more major tennis like Wimbledon, tiny connections to that NBA and a little NHL, major college football, Kentucky Derby, aquatics and Olympic Games, that sparkling little city sits around halfway between Los Angeles and Palm Springs on Interstate 10. – Obrey Brown

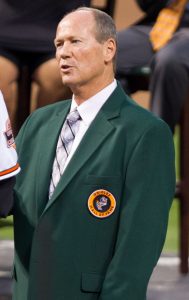

Jim Weatherwax, who played in the fabled Ice Bowl game against Dallas, had a hand in helping Green Bay win its first two Super Bowl titles.

Brian Billick basked in the glow of his name joining names like Landry and Shula, Noll and Parcells, Walsh and Gibbs on the Lombardi Trophy. Curiously, eventual five-time Lombardi Trophy celebrant Bill Belichick would join that list after Billick.

Patrick Johnson, who caught a pass in Super Bowl XX, nearly made a diving catch for a touchdown in that same game against the New York Giants.

Welcome to A Redlands Connection-Super Bowl edition. That trio of former Redlands football players – Johnson (1994 graduate), Weatherwax (1961) and Billick (1972) – has surfaced in America’s greatest sporting spectacle.

It’s easy to break it down, too. Johnson’s speed. Weatherwax’s strength. Billick’s brains. It culminated with a spot in pro football immortality.

Johnson’s path to the Super Bowl might have been the shortest. He graduated from Redlands in 1994, committed to the University of Oregon and was selected by Baltimore in a second round pick in 1998’s NFL draft .

Weatherwax left Redlands after graduating in 1961, headed for Cal State Los Angeles before transferring to West Texas A&M in Canyon, Texas. Green Bay took him in round 11 during that 1965 NFL draft.

Billick’s path took him to Air Force Academy, eventually transferring to Brigham Young University. He was drafted by Dallas, but his career wasn’t as a player. He coached at Redlands, in San Diego, pushing onto Logan, Utah before Stanford in Palo Alto before surfacing as an assistant coach for Denny Green in Minnesota.

By 1999, Billick was named head coach in Baltimore.

It almost seems like pro football didn’t exist before 1967. It delivered a National Football League champion against an American Football League champion for professional football’s world title. It was a first.

In those seven years since AFL play had been developed, that league held its own championship. The Houston Oilers, Dallas Texans (future Kansas City Chiefs), San Diego Chargers and Buffalo Bills had won AFL titles.

NFL titles during that same span mostly went to Green Bay from 1961, 1962 and 1965 with Philadelphia, Chicago and Cleveland also winning NFL championships during those seasons before Super Bowl actions started in 1967.

SUPER BOWL ERA BEGINS

By that 1966 season, with 1967 showcasing its first AFL-NFL title game, Super Bowl’s era was born. In fact, Super Bowl terminology had yet to become adopted. That game was billed simply as an AFL-NFL Championship Game.

Green Bay going up against Kansas City was quite a spectacle. It was AFL’s best team going up against the NFL’s best. Vince Lombardi’s Packers playing Hank Stram’s Chiefs.

Redlands had a representative right in that package. It was none other than Weatherwax, known back in Redlands as “Waxie.”

Weatherwax, for his part, played plenty in during second half in both championship games. He was seen spelling starters Ron Kostelnik and Henry Jordan on a few plays in that first half of Super Bowl II.

That particular showdown had been set up by that famous Ice Bowl game of 1967. That NFL Championship showdown came down to Bart Starr’s last-second quarterback sneak for a touchdown that beat Dallas on Green Bay’s “frozen tundra.”

It’s so well-known these days that winning play hinged on blocks from Packers’ center Ken Bowman and guard Jerry Kramer, who blocked Cowboys’ defensive tackle Jethro Pugh. That play, that win ultimately led Green Bay into its second NFL-AFL championship, now dubbed a Super Bowl, this one against Oakland in Miami.

Pugh, incidentally, was picked in that 1966 NFL draft five players ahead of Weatherwax in the 11th round.

Green Bay, of course, won both “Super Bowl” games. The Packers, thus, set NFL history in virtual stone.

“That second Super Bowl was Lombardi’s last game,” Weatherwax told me several years later. “You should’ve heard the guys before that game, Kramer in particular. ‘Let’s win it for the old man.’ That’s what he was saying. Looking back, you couldn’t do anything but think that was special.”

AFL, NFL TACTICS LED TO MERGER

It was that first Super Bowl, however, that proved itself worthy of attention.

Referees in that first Super Bowl: Six overall, including three AFL and three NFL, including head referee Norm Schachter, who started his officiating career 26 years earlier. He was an English teacher in, of all places, Redlands.

The networks: The AFL’s NBC would be telecasting against the NFL’s CBS. Jim Simpson was on the radio.

Weatherwax, meanwhile, was playing behind the likes of Willie Davis and Bob Brown, Kostelnik and Jordan – Green Bay’s legendary defensive linemen. The Redlander gave a short chuckle as “The Hammer.”

Weatherwax said, “I can’t really say what happened out there.”

What happened? “The Hammer” was Chiefs’ secondary defender, Fred Williamson, who predicted he’d “hammer” Packers’ wide receivers during that initial championship games. It was Williamson himself that got knocked out of that game, Waxie noted.

Translation: He knew what happened, all right.

When Packers’ placekicker Don Chandler sent his kick toward Kansas City’s Mike Garrett, it was Weatherwax who drove the onetime college Heisman Trophy winner out of bounds.

Credited with a tackle. First in a Super Bowl.

There were a few times that Weatherwax, part owner of restaurant in Orange County, later moving to Colorado, sat next to my desk. Earlier, he visited with Jeff Lane at that same office. Waxie showed up in Redlands visiting old friends.

Part of those visits included stopping by Redlands’ local newspaper. This dates back to the 1980s and 1990s. Sharing stories. Sharing memories. Showing off his championship jewelry. Great guy. Helpful. Willing to talk.

It was a huge part of a Redlands Connection.

Part 2 – About Super Bowl XXXV tomorrow.