A Redlands Connection is a concoction of sports memories emanating from a city that once numbered less than 20,000 people. From pro football’s Super Bowl to baseball’s World Series, from dynamic soccer’s World Cup to golf’s and tennis’ U.S. Open, major auto racing, plus NCAA Final Four connections, Tour de France cycling, more major tennis like Wimbledon, tiny connections to that NBA and a little NHL, major college football, Kentucky Derby, aquatics and Olympic Games, that sparkling little city sits around halfway between Los Angeles and Palm Springs on Interstate 10. This story’s lightning baseball player, a brilliant second baseman and base stealer, has connected in a far away expectation anyone could imagine. – Obrey Brown

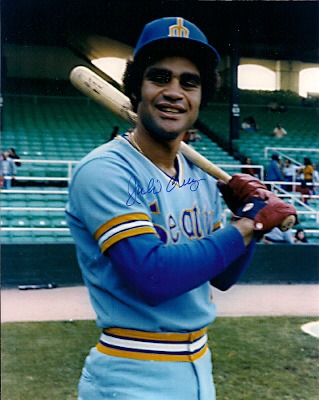

I MET JULIO CRUZ A NUMBER of times, including twice in the clubhouse at Anaheim Stadium when he was a member of the Seattle Mariners, the other after he’d been traded to the Chicago White Sox. The other times came years later. He had long since retired.

Cruz’s onetime home city, which was Redlands, enjoyed a return as a youth demonstration about baseball. Someone had convinced him to come back for a pre-season baseball clinic at Community Field in 1994.

Brooklyn-born. Moved to Redlands. Graduated. Headed for San Bernardino Valley College. Signed as a free agent. California Angels. That was just the beginning.

Cruz hit .237 over 10 MLB seasons. He is, indeed, a Hall of Famer. In Redlands. Considering that Cruz, a 1971 RHS graduate, was the first-ever Terrier to reach the major leagues, there’s not a single belief he couldn’t have been inducted in that campus’ sports Hall of Fame. The guy has taken part in some of baseball’s greatest moments.

Sports Editor Jeff Lane, my predecessor at the Redlands newspaper, had done plenty on Cruz during his five-year stint on that publication. He was a longshot product – never drafted, never spotted in huge high school or college games, rarely reported to major league scouts. To that point, no Redlands player had ever drifted their way from that city into the major leagues.

Ed Vande Berg, a southpaw pitcher, would be next. Another Redlands product who didn’t pick up top-level play until he showed up at San Bernardino Valley College. By his sophomore season, Vande Berg was named State Player of the Year after posting an 18-1 mound record.

Who’d have believed that two ex-Terrier high schoolers would wind up playing on the same major league teams – Cruz and Vande Berg eventually became teammates with the Mariners for a handful of seasons.

Cruz, a 1972 Redlands High graduate, played at nearby San Bernardino Valley. Though undrafted, he was signed by the California Angels on May 7, 1974 as a free agent after his performance at a longshot tryout held at UCLA.

Yes, the Angels sent Cruz into their minor league system. As a 19-year-old, he batted .241 for Idaho Falls of the Rookie League in 1974. He went right up the Angels’ chain – .261 for Quad Cities, .307 for Salinas, .327 for El Paso and .246 for Salt Lake City at age 22.

Sports Editor Jeff Lane, my predecessor at the Redlands newspaper, had done plenty on Julio during his five-year stint on that publication. Julio was a popular product. To that point, no Redlands player had ever drifted their way from that city into the major leagues.

Ed Vande Berg, a southpaw pitcher, would be next. In fact, the two would eventually become teammates in Seattle.

Julio, a 1972 Redlands High graduate, played at nearby San Bernardino Valley. Though undrafted, he was signed by the California Angels on May 7, 1974 as a free agent after a tryout held at UCLA.

The Angels sent Cruz into their minor league system. As a 19-year-old, he batted .241 for Idaho Falls of the Rookie League in 1974. On he went, right up the Angels’ chain – .261 for Quad Cities, .307 for Salinas, .327 for El Paso and .246 for Salt Lake City at age 22.

EXPANSION — A REAL BREAK FOR CRUZ

The American League, about to expand from 10 teams to 12 teams by 1977, had to make players available in a draft pool. Cruz was left unprotected by the Angels, who had ex-Red Sox second baseman Jerry Remy on their MLB level. For that position, the Angels didn’t need Cruz.

While Cruz batted .366 for Hawaii of the Pacific Coast League – stashed then with the Padres’ chain while Seattle organized its minor league system – it wouldn’t be long before he got his shot in the majors.

On Nov. 5, 1976, Cruz had been the 52nd player taken in the American League expansion draft when two new franchises appeared – Seattle and Toronto.

Suddenly, he was a “sudden” Mariner.

In a curious draft footnote, pitcher Butch Edge was taken by Toronto out of Milwaukee’s chain. Edge would eventually wind up in Redlands years later as the University of Redlands’ men’s golf coach. Other players taken in the draft included Pete Vuckovich being plucked away from the White Sox by Toronto. Vuckovich eventually wound up with the Brewers, winning the 1982 Cy Young Award.

Edge, at least in 1979, and Vuckovich would eventually wind up playing against Cruz. It was the Redlands-based player who turned into a Seattle stalwart. Longing for star players, Cruz’s base-stealing skills turned him into a popular Mariner.

He stole 59 bases in 1978, then swiped 49, 45, 43 and 46 bags over the next four seasons. What’s lost in those numbers is that he stole 49 in just 107 games in 1979. During that MLB strike-shortened 1981 season, Cruz swiped 43 times in 94 games.

If there was a weakness to his game, Cruz’s on-base-percentage was awfully low – his highest at .363 in ’79 – but he put a lot of bunts in play to try and get on base.

There were some decent teammates in Seattle – Al Cowens, Richie Zisk, Dave Henderson, Willie Horton, Bruce Bochte, Ruppert Jones, among others – with pitchers like future White Sox teammate Floyd Bannister and Hall of Famer Gaylord Perry playing in Seattle with Cruz.

In fact, Cruz was on the field on May 6, 1982 when Perry (10-12 that season) won his 300th game. He beat the Yankees at the Kingdome to notch this milestone victory. Julio, not to confuse anyone with his shortstop mate Todd Cruz, scored a run, laid down a sacrifice and threw out four Yankees and put out two more.

It was Julio, in fact, who fielded the grounder off fellow second baseman Willie Randolph for the final out.

In fact, Julio was on the field on May 6, 1982 when Perry (10-12 that season) won his 300th game. He beat the Yankees in the Kingdome to notch this milestone victory.

It was Cruz, in fact, who fielded the grounder off Willie Randolph for the final out.

TRADED TO THE CHISOX

On June 30, 1983 — MLB’s trading deadline — Seattle swapped Cruz to the Chicago White Sox for second baseman Tony Bernazard. The results of that trade might’ve been the foundation for the ChiSox vaulting to an American League Western Division title by 20 games over Kansas City.

That ’83 season was convincingly his best season – 160 games between his two seasons, 130 hits, 57 stolen bases and 24th on that year’s MVP balloting. That season was won by Baltimore shortstop Cal Ripken, Jr., whose team knocked off the ChiSox in the playoffs.

Incidentally, White Sox catcher Carlton Fisk (3rd), Baines (10th), LaMarr Hoyt (13th), Greg Luzinski (17th), Richard Dotson (20th) and Rudy Law (21st) got MVP voting support ahead of Cruz.

“Let’s Do It Again” was the theme for 1984. What the ChiSox did was fall back to fifth place, 14 games under .500. General Manager Roland Hemond, who leveraged the Bernazard-for-Cruz swap, brought in pitcher Ron Reed and practically stole future Hall of Famer Tom Seaver from the Mets.

Their contributions weren’t enough to offset poor showings, perhaps reflected by 1983 ace pitchers Hoyt (13-18) and Dotson (14-15) one season later.

There were 54,032 fans at Yankee Stadium when Seaver beat the Yankees for his 300th career win. Cruz, in the dugout batting less than .180, wasn’t part of that ChiSox 4-1 on-field triumph.

On the field, though, were Hall of Famers like Rickey Henderson and Dave Winfield, MVP Don Mattingly and, of course, Seaver. Managers Tony La Russa and Billy Martin squared off against each other.

One night later, Cruz was back in the lineup, going 2-for-2 off Ron Guidry, caught stealing by Yankee catcher Butch Wynegar.

The 1985 White Sox club bounced back to win 85 games and actually led the division in June. By 1986, the club was in disarray with new general manager Ken Harrelson, who had replaced both Hemond, and manager Jim Fregosi. It would be four more seasons before the Chicago White Sox finished over .500.

Cruz was living off an impressive free agent contract that was signed in December 1984, a six-year deal between $3.6 and $4.8 million. He never completed it. He played in 1,156 career games; swiped 343 bases; don’t forget an impressive .982 defense at second base.

Released by the White Sox in July 1987, Cruz signed as a free agent with Los Angeles. But the 1987 Dodgers already had a second baseman. Steve Sax would go on to lead his team to a World Series title a year later. Cruz, who drew release, never actually played for the Dodgers. This onetime Terrier was finished.

Ten years of his MLB career was now complete.

A TERRIER HALL OF FAME RETURN

He was part of the second class of Hall of Fame inductees at his former Redlands high school. In fact, Cruz unwittingly opened the door to a humorous line given by fellow inductee Brian Billick, of Super Bowl football fame.

Cruz spoke emotionally about his Terrier days. The memories. Boy, he had fun. The teams he’s played on. There was some success. The Terriers, with Cruz in the lineup, won the first Citrus Belt League title in 1971 — 44 years after their previous championship from 1927.

At the Redlands Hall of Fame podium, Cruz shared a memory. “Just being in the showers with guys like Brian Billick was a thrill. Those were highlights for me. I’ll never get over that.”

Billick? Billick, the Terrier great defensive back and QB who was head coach of the 2001 Baltimore Ravens when they won the Super Bowl, was also being inducted that same night at the University of Redlands.

In fact, Billick broke the crowd up when he said, “Cruz, it’s amazing to me that you felt like the highlight of your high school career was taking a shower with me.”

Those Hall of Famer viewers started busting up.

A few years before that Hall of Fame moment, Cruz, along with ex-major leaguer Rudy Law and Hall of Fame pitcher Ferguson Jenkins took part in a baseball clinic at Community Field. Former Pirates and Yankees pitcher Dock Ellis was also on hand.

Dozens and dozens of area youth showed up for that historic event at the corner of Church Street and San Bernardino Avenue. This was a rare moment for local youth. Dads let their kids know who this guy was: Cruz, of Redlands. Former major leaguer. Little guy. Second baseman. Switch hitter. Lots of speed. Wanna get your kids into the big leagues? Listen. Watch.

Jenkins, Ellis and Law couldn’t have been more classy. Cruz, the ex-Terrier, knew he was at home. Those players gave tips. They shared stories. They shook hands. Smiled. They signed autographs.

Cruz eventually became a coach. Broadcasting games eventually came up for the Spanish-listening Mariner fans, Cruz taking his Brooklyn-to-Redlands-to-Seattle-to-Chicago travels really well.

Why not a Terrier Hall of Famer? He fit the mold. Came into that Hall that same season as Brian Billick, the ex-Terrier football player who led the Baltimore Ravens to the 2001 Super Bowl. Billick and Cruz even shared the same roster as Terrier basketball players during those early 1970s.

While playing with, or against, MLB Hall of Famers like Fisk, Perry, Seaver and Baines, Cruz wound up playing for one Cooperstown-bound manager — La Russa.

It was, if anything, a diamond-style Redlands Connection.

*****

Cruz was 67 when he died of cancer in February 2022. There were a few chats we had together in years leading to that moment. It was 15 years before he died that his first wife, Rebecca, died from cancer. He was married to Mojgam upon his death.